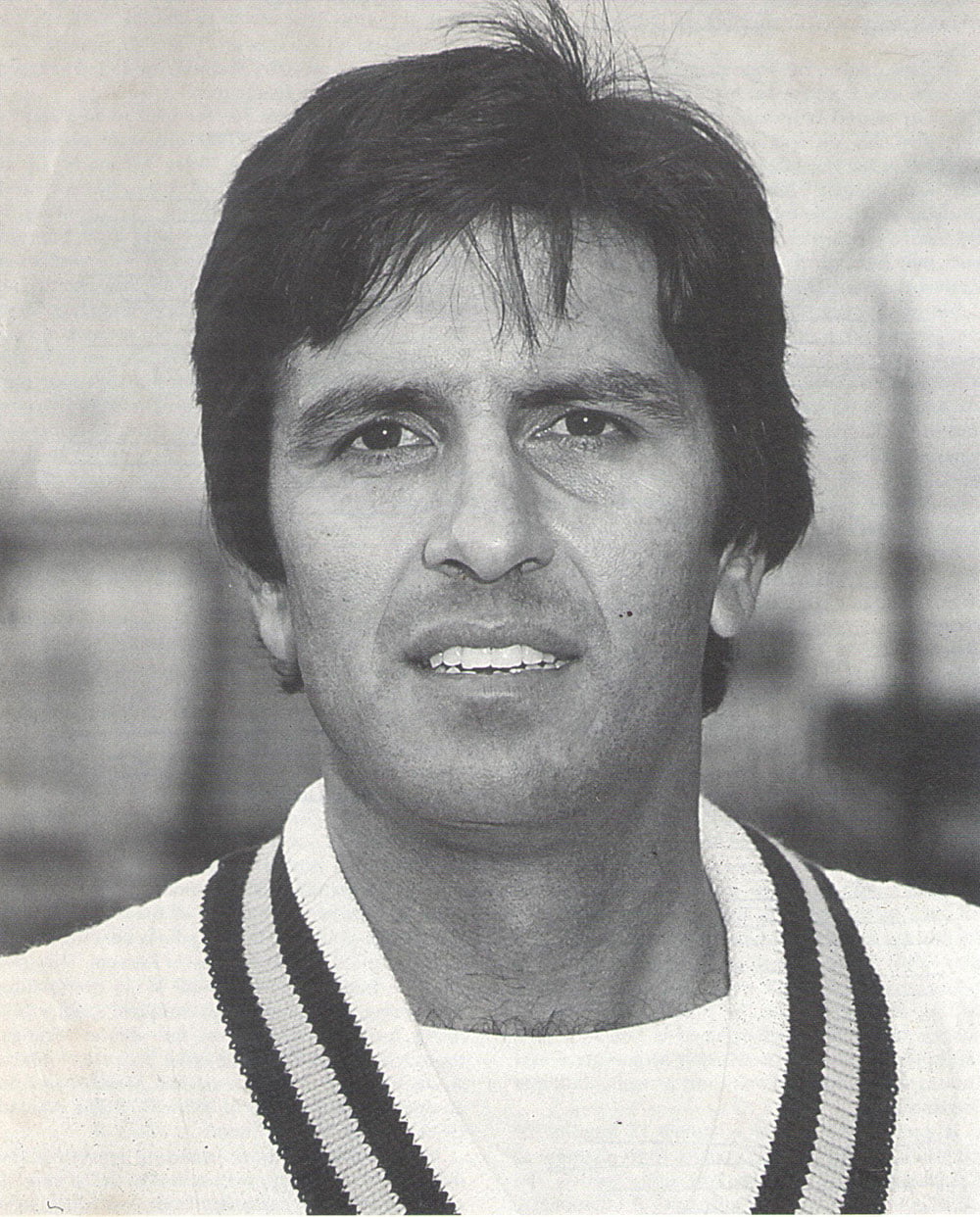

The El Magnifico of cricket. A cricketer and a gentleman. An aristocrat in true sense. Among the very last of cricket’s glorious and noble heritage of gentlemen. If there is one Pakistani cricketer from three hundred plus to have donned the country colors who fits the bill for all these descriptions and truly lived up to the spirit embedded therein, it is none other than the mighty, mystical, majestic persona of Majid Jehangir Khan.

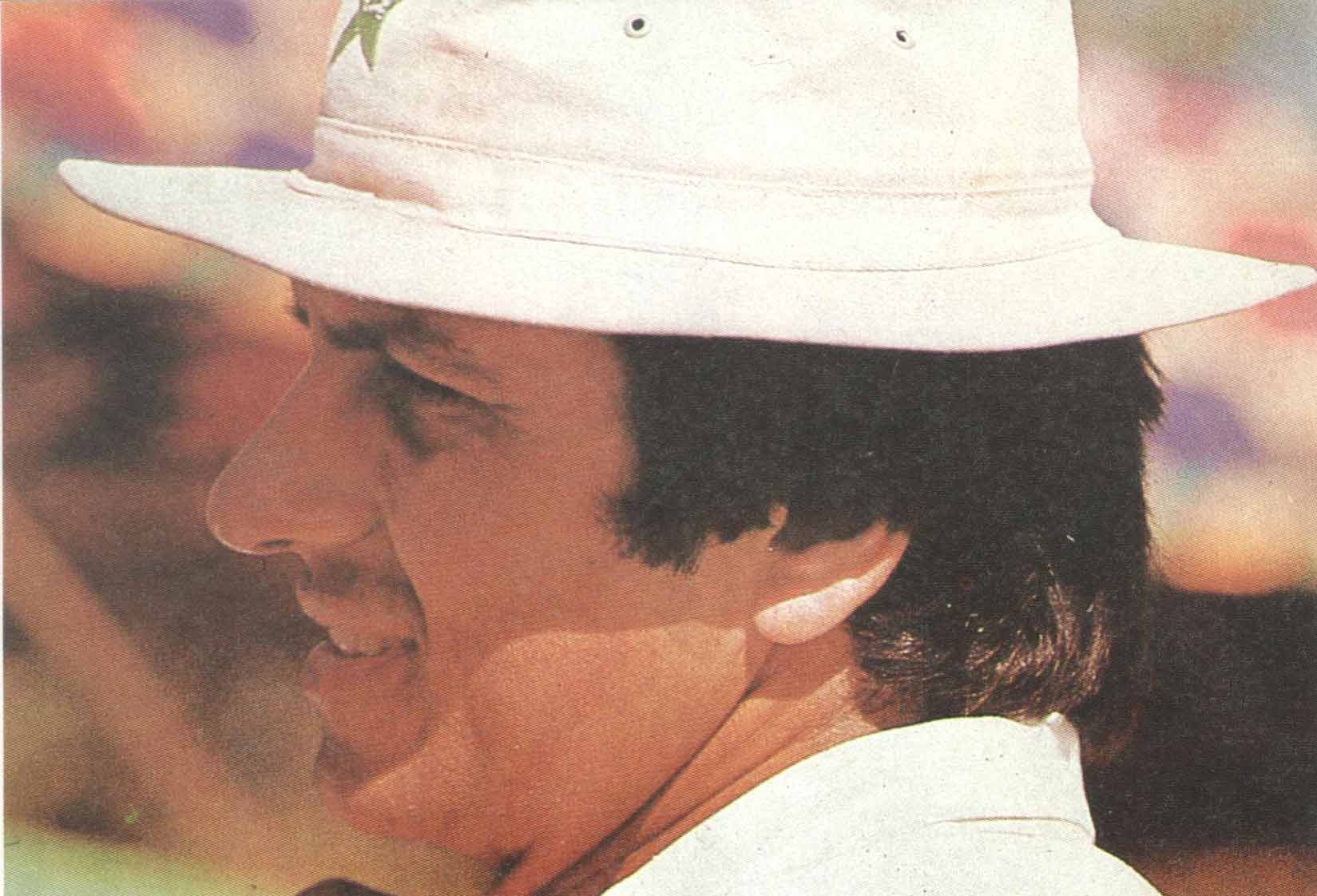

For those who have been fortunate enough to witness his presence on a cricketing green whether wielding his bat like a magic wand wearing that faded gardener’s hat or standing serenely at the first slip or delivering his innocuous looking off-breaks from a short run up with sleeves buttoned, there was be no sight more graceful, beholding and enriching. It just seemed that the ball just obeyed Majid. He caressed it ever so gently and it sped to the boundary like a Lewis Hamilton driver F1 car. No brutal force, just hand-eye coordination and sheer timing. A joy to watch.

In the seventies fast bowlers roamed the planet earth like the pre-historic Tyrannosauruses. Almost all the top nations of the world possessed armory worthy of initiating a cricketing world war. The Australians had vicious duo of Lillee and Thomson aided by Walker, Gilmour, Hogg and Pascoe. Just to name the entire West Indian thunder squad led by Andy Roberts and Michael Holding will consume at least ten lines.

Snow, Willis and Old from England, Hadlee, Kapil, Imran, Sarfraz and the South African Procter and Le Roux were all menacing and mean in their own right. To be a batsman in the years before the advent of protective headgear and face such a battery of unrelenting pacers took a lot of courage and resilience. And to open the batting against such barbaric forces was bordering on madness.

And finally to be regarded as the top most and fearless opener and placed among the top three batsmen in the world meant a pinnacle worth its place in the entire cricketing history. In seventies that honor went to Majid who along with Viv Richards, Barry Richards and Greg Chappell was regarded as the finest exponent of the art of batsmanship of that era and as the ultimate adversary for the fast bowling demons.

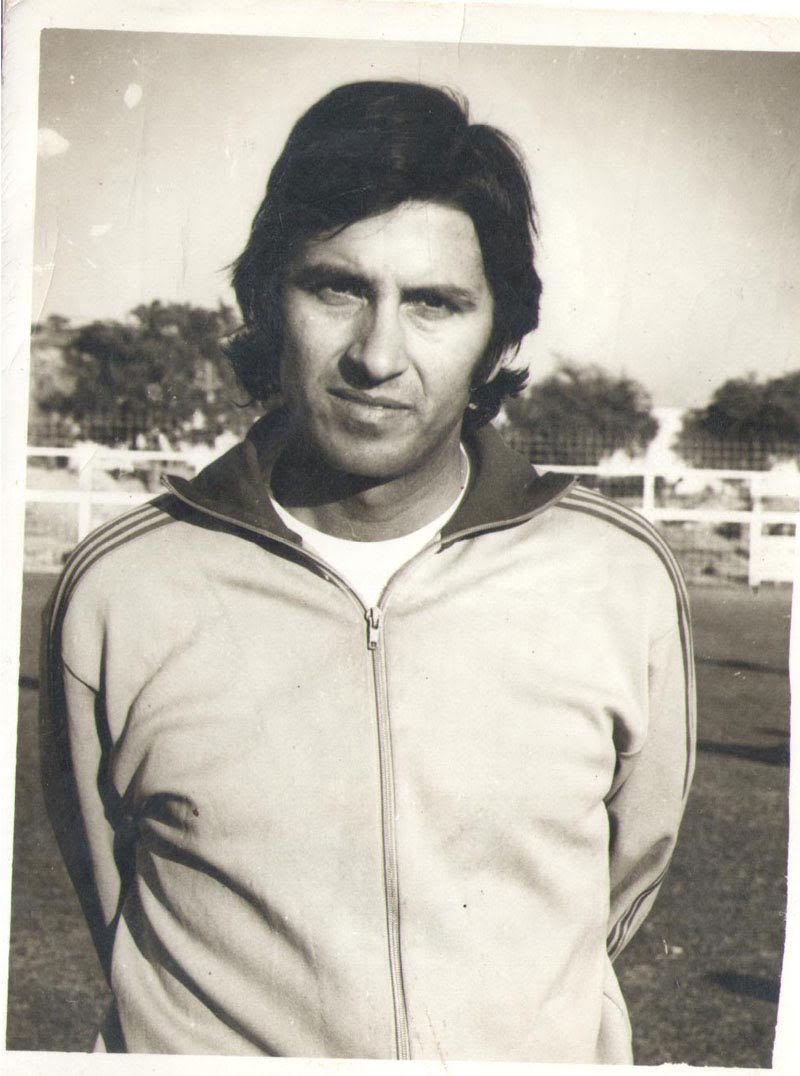

For someone who started his international career as an opening bowler the transformation into a world class batsman was remarkable and with few parallels in cricket history. Majid with a bat in his hand was simply magic and in a league of his own. The key in his evolution as a batsman was Majid’s exposure to English conditions in his formative years.

The time he spent at Glamorgan and Cambridge reinvented Majid. The talent was always there as exhibited in flashes of brilliance like his whirlwind 89 minutes 147 against Glamorgan in a Pakistan tour match but the rise as a top notch player came much later. That innings forced Glamorgan think tank to sign up Majid as their overseas player and he was instrumental in their 1969 win in the County Championship. In his days at Cambridge he opted to lead his University against the 1971 Pakistani touring side and emerged surprised victors.

The going on international front was not that easy though. In his first eight years after making his Test debut Majid had appeared only in 13 Test matches and scored just above 400 runs; nothing much to brag about indeed. Then he arrived with a bang at Melbourne with a classy 158 against the spiteful duo Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson and from onwards there was no looking back.

In early seventies, Pakistan side was struggling to find a suitable opening partner for left-handed Sadiq Mohammad. Old timers like Mohammad Ilyas, Aftab Gul and even Nasim-ul-Ghani had a go at this slot along with young guns like Talat Ali and Shafiq “Papa” but no one was able to cement his place at the top.

At the same time, the middle order was loaded with rich talent like Zaheer Abbas, Mushtaq Mohammad, Asif Iqbal and up and coming youngsters like Wasim Raja and Javed Miandad. So when Majid got promoted to the opening role on team management’s request midway through the 1974 tour of England, not only it heralded the best ever opening combo for Pakistan, it also created a vacancy in the middle order.

His first outing as an opener yielded a top score of 48 in a team total of 130 on a dicey track against “Deadly” Derek Underwood and Majid followed it up with a masterly 98 on a placid Oval wicket to settle the opening issue for a long time to come.

Majid always relished the pace challenge and loved to score in the lion’s den. His record against Australian and the West Indian attacks on their home turfs was remarkable, to say the least. Arguably the best player of fast bowling ever to be produced by Pakistan along with the big burly Inzamam, Majid’s prowess was at its peak during the 1976-77 season. Not in terms of accumulating runs only but more so in the way he made them. Made all others batting around him look like labourers involved in forced fatigue.

A century before lunch on the first day of the Test at Karachi against a Kiwi pace attack featuring Richard Hadlee, Lance Cairns and Richard Collinge was just an indication of things to follow. To date, only six batsmen including Australian maestros Don Bradman and Victor Trumper have achieved this unique distinction in Test matches.

In Australia Majid had another fruitful series culminating in his moral victory over Australian spearhead Dennis Lillee who had sworn to knock off Majid’s hat. Majid not only hooked Lillee for an effortless six in midst of a fiery opening burst as Pakistan were chasing a small matter of 32 runs to record their first win on the Australian soil, but he was also gracious enough to hand over his famous gardener’s hat to Lillee in the post-match presentation ceremony at Sydney.

The Australian conquest was followed by an even more adroit display on the Caribbean Islands where Majid recorded his highest test score of 167 while amassing 530 runs against Andy Roberts, Joel Garner, Colin Croft and their other sidekicks like Bernard Julian and Vanburn Holder.

Majid’s batting proficiency was not limited to handling fast and furious only. Many critics including Indian skipper Bishen Bedi regarded him as the best bad wicket player for the fiendish spinning tracks. His crafty handling of Underwood on rain-soaked tracks was a testimony to this honor and his masterly 89 on Karachi’s dusty turner against Australia’s Ray Bright was an epic carved out when 21 other players including skippers Greg Chappell and Javed Miandad were finding it difficult to survive.

Despite his laid back appearance, Majid was an exceptionally good slip fielder who scooped up 69 catches in his 63 Test matches, a majority of them at first slip, which remained a Pakistan record for a long while. He was a good hockey player and used to lead team physical drills as a PT instructor on international trips in the days before the advent of specialist coaching staff.

At Kingston Jamaica in 1977 Majid took over the wicket keeping gloves when Wasim Bari got injured while batting and picked up four catches with gloves on. When Bari came back later in the innings he picked up another three to make a then record total of seven catches by a wicketkeeper in an innings.

Majid was equally adept at the limited overs version of the game. When ODIs came into vogue, Majid fired Pakistan’s first ever One-day International century against England. His proficient partnership with Zaheer Abbas in the 1979 World Cup semifinal almost turned the table on eventual winners West Indies.

Majid’s family’s legacy in Pakistan cricket is the most impressive and star studded one. His father Jehangir Khan was an opening bowler for India in the 1930s and his son Bazid also played a Test match making their family the second, after the Headleys, to have three consecutive generations of Test cricketers.

His cousins Javed Burki and Imran Khan both captained Pakistan and his uncle Baqa Jillani was a first-class cricketer. Majid is also married to Javed Burki’s sister. In his later years Majid remained the Director Sports of Pakistan’s national television for many years and had brief stints as ICC match referee and the PCB’s CEO in the late nineties.

Imran however was the reason for abrupt termination of Majid’s international career when he conscientiously preferred Mansoor Akhtar over Majid to appear as a transparent and performance oriented leader.

Majid only played two Test matches under Imran before walking back to pavilion at his home ground for the last time. A rather unceremonious end to an otherwise glorious career. All good things come to an end.