My personal top three preferences to watch cricket being played, are:

1. At the ground, with a good view of the pitch, and the holistic luxury of the virtually 360 degree scan.

2. Radio commentary, evoking the unrivalled power of the unseen, as so unforgettably rendered in English by Omar Kureishi, Jamshed Marker and John Arlott in the 1950s, 60s, 70s and later by Iftikhar Ahmed, Chishty Mujahid and Humayun Shahzad. And by Munir Hussain and Bashir Khan in Urdu.

3. Reading a balanced descriptive report the next day in a printed newspaper.

The fourth, and least liked, and yet, now most often used, is cricket via TV, and the same on internet websites and social media. Which is also the most prevalent way of watching the game — in Pakistan and around the world. The major reason for this being the least personally preferred is the contamination of the viewing experience by commercial advertising. The signs on the ground are there even in the first favourite: streamers, placards, bill-boards, words and signs on players’ apparel, even announcements of sponsors’ names.

On radio too, there are mid-breaks for vocal brand messages. In newspapers as well, advertising has crept into spaces next to scorecards.

Yet advertising on cricket TV is a domineering menace of its own kind. Abrupt switch-aways from the end of every over to a flurry of short bursts about numerous brands. With no regard for a commentator being cut-off in mid-sentence. Nor for the viewers being deprived of listening. The sleeves and backs of players’ tops brandishing advertisers’ names as noticeably as the name of the players’ country on the front side.Brands popping up on giant screens in stadiums when the third umpire or referee calls for replays.

Flashes of brand names with each super-imposition about sixes, or fours or other aspects of scores. Backdrops for brief interviews with the two captains or star players crammed full of logos, symbols, names of sponsors. Intrusive exposures of visuals while experts — dressed up in identical uniforms! —discuss an ongoing match.

The cumulative impact disrupts continuity of attention, damages coherence in narratives, prevents sustained dialogue and exchanges, even repels attraction to the very name being so crudely promoted. But the effect goes beyond single moments, individuals, innings and matches. Whole frameworks, organizations and institutions have become willing partners in this plunge into the abyss of excess. From teams to leagues, from country regulatory boards to international regulatory agencies — even governments of states have cooperated to place commerce on the throne.

Though India can take justified pride in it’s team’s remarkable winning streak in the 2023 World Cup, it’s own regulatory body is viewed by non-partisan, non-Pakistani analysts as exerting an unhealthy, unseemly, almost strangulating grip to shape ICC decisions because of the enormous financial weight that the Indian commercial cricket market has acquired. Such asymmetry directly contradicts the principles of equality and equity for all countries in any multi-lateral sports entity.

Perhaps this current outcome of rampant commercialism began with Kerry Packer in the early 1970s when players were belatedly offered the chance to earn what they truly deserved, instead of the pittances and paltries they used to be previously paid. However, step by step, year by year, the original spirit and character of the contest that was termed “a gentleman’s game ” were allowed to be overcome by the seduction of lucre — to it’s present state of what has de facto become “a greedman’s game “.

Advertisers and mass media, without ignoring some positive and constructive contributions they have made to the public interest, and in the latter case, especially Tv channels have willfully colluded in this self-seeking pursuit of profits from the playground. Which brings this writer to confession time. Back in 1978, soon after Pakistan Tobacco Co. Ltd kindly invited MNJ Communications, the advertising firm of which I was CEO to become their advertising consultants, the decision was taken to associate their Wills brand with cricket. Parallel to this was a similar decision by India Tobacco Co Ltd to do the same in our neighbouring country. Both companies were part of the multi-national British American Tobacco group, with varying levels of shares held by locals.

As the advertising of cigarettes was still permitted on TV and radio one overcame a guilty conscience about helping promote a product increasingly held to be unhealthy, if not lethal for many, by obtaining refuge under the “legality “of the work. And it helped that the PTC account was one of the largest and one of the most reputed in the country in those years.

Under the benign chairmanship of Syed Nizam Shah, the outstanding marketing team of PTC was led by the debonair, intelligent Riaz Mahmood (alas, now departed), with the deceptively quiet, valuably insightful Saquib Hameed and the meticulously observant, sharply focused Taher Memon. The last named has carefully chronicled the crucial role of PTC , and others , in making cricket a national sport to equal and then overtake hockey in his book ” Another View ” . That ascendancy became possible only through PTV and PBC which took the images and sounds of cricket into the nooks and corners of the whole country. At MNJ we wrote, directed and produced numerous TV commercials with the pay-off line “Wills and cricket go together “.

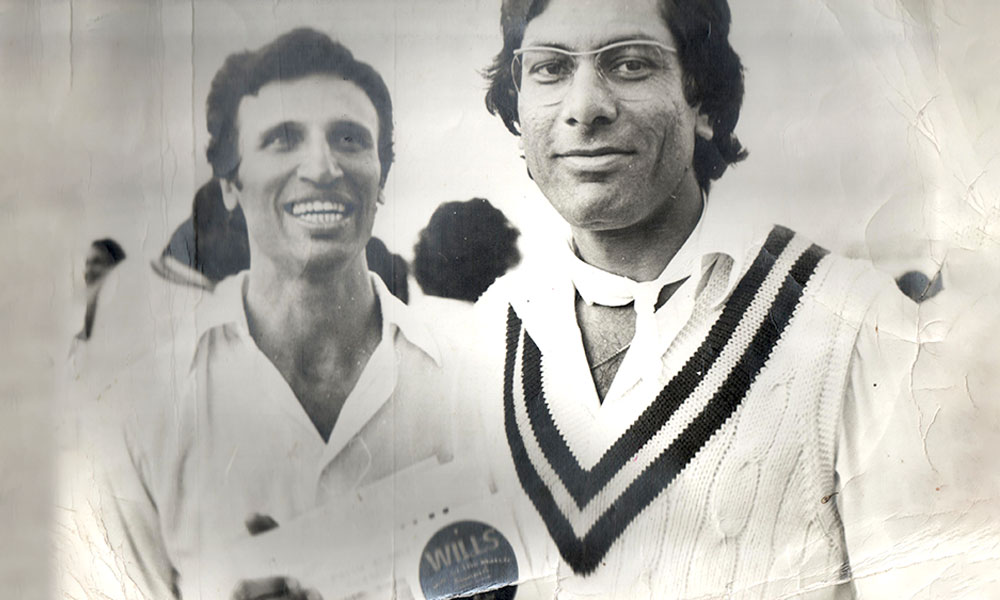

During the 1979 World Cup in England, this writer and the team filmed 5 leading Pakistani cricketers — Asif Iqbal, Zaheer Abbas, Majid Khan, Javed Miandad and a fast-rising all-rounder named Imran Khan for a series of five mini-portraits that became instantly widely popular through frequent screenings on PTV.

YouTube in 2023 gives access to at least 2 of them. The players were depicted in a range of family and play situations but never shown holding a cigarette, leave alone smoking one. Yet the synonmity of the brand and the player’s name was explicit and extensive, in return for a reasonable fee. Compared to today’s spoils a small sum. Current fees reportedly have thoroughly spoilt players, however well-deserved.

The popularization of cricket was greatly helped by a subtle aspect of General Zia ul Haq’s information policy: keep the attention of the masses diverted for long hours every day from the darkness of martial law, the execution of Z.A. Bhutto and it’s aftermath, MRD, etc. and from other plots contrived by the regime — by transmitting live coverage of a game that took hours and hours every day, not the fleeting 90 minutes of hockey or football.

For the record: Though this writer can rightly be charged for being an active party to the original sin , none of us involved in that initial phase of commercializing cricket wanted the creature of advertising to become a colossus on the field and in the media that it has become today. Can a tide be reversed, particularly when no state or private institution today in 2023 seems interested in moderating the surrender to pitches by brands while the pitches on which this addictive game is played, and the attendant values, receive far less attention.