My personal top three preferences to watch cricket being played, are:

1. At the ground, with a good view of the pitch, and the holistic luxury of the virtually 360 degree scan.

2. Radio commentary, evoking the unrivalled power of the unseen, as so unforgettably rendered in English by Omar Kureishi, Jamshed Marker and John Arlott in the 1950s, 60s, 70s and later by Iftikhar Ahmed, Chishty Mujahid and Humayun Shahzad. And by Munir Hussain and Bashir Khan in Urdu.

3. Reading a balanced descriptive report the next day in a printed newspaper.

The fourth, and least liked, and yet, now most often used, is cricket via TV, and the same on internet websites and social media. Which is also the most prevalent way of watching the game — in Pakistan and around the world. The major reason for this being the least personally preferred is the contamination of the viewing experience by commercial advertising. The signs on the ground are there even in the first favourite: streamers, placards, bill-boards, words and signs on players’ apparel, even announcements of sponsors’ names.

On radio too, there are mid-breaks for vocal brand messages. In newspapers as well, advertising has crept into spaces next to scorecards.

Yet advertising on cricket TV is a domineering menace of its own kind. Abrupt switch-aways from the end of every over to a flurry of short bursts about numerous brands. With no regard for a commentator being cut-off in mid-sentence. Nor for the viewers being deprived of listening. The sleeves and backs of players’ tops brandishing advertisers’ names as noticeably as the name of the players’ country on the front side.Brands popping up on giant screens in stadiums when the third umpire or referee calls for replays.

Flashes of brand names with each super-imposition about sixes, or fours or other aspects of scores. Backdrops for brief interviews with the two captains or star players crammed full of logos, symbols, names of sponsors. Intrusive exposures of visuals while experts — dressed up in identical uniforms! —discuss an ongoing match.

The cumulative impact disrupts continuity of attention, damages coherence in narratives, prevents sustained dialogue and exchanges, even repels attraction to the very name being so crudely promoted. But the effect goes beyond single moments, individuals, innings and matches. Whole frameworks, organizations and institutions have become willing partners in this plunge into the abyss of excess. From teams to leagues, from country regulatory boards to international regulatory agencies — even governments of states have cooperated to place commerce on the throne.

Though India can take justified pride in it’s team’s remarkable winning streak in the 2023 World Cup, it’s own regulatory body is viewed by non-partisan, non-Pakistani analysts as exerting an unhealthy, unseemly, almost strangulating grip to shape ICC decisions because of the enormous financial weight that the Indian commercial cricket market has acquired. Such asymmetry directly contradicts the principles of equality and equity for all countries in any multi-lateral sports entity.

Perhaps this current outcome of rampant commercialism began with Kerry Packer in the early 1970s when players were belatedly offered the chance to earn what they truly deserved, instead of the pittances and paltries they used to be previously paid. However, step by step, year by year, the original spirit and character of the contest that was termed “a gentleman’s game ” were allowed to be overcome by the seduction of lucre — to it’s present state of what has de facto become “a greedman’s game “.

Advertisers and mass media, without ignoring some positive and constructive contributions they have made to the public interest, and in the latter case, especially Tv channels have willfully colluded in this self-seeking pursuit of profits from the playground. Which brings this writer to confession time. Back in 1978, soon after Pakistan Tobacco Co. Ltd kindly invited MNJ Communications, the advertising firm of which I was CEO to become their advertising consultants, the decision was taken to associate their Wills brand with cricket. Parallel to this was a similar decision by India Tobacco Co Ltd to do the same in our neighbouring country. Both companies were part of the multi-national British American Tobacco group, with varying levels of shares held by locals.

As the advertising of cigarettes was still permitted on TV and radio one overcame a guilty conscience about helping promote a product increasingly held to be unhealthy, if not lethal for many, by obtaining refuge under the “legality “of the work. And it helped that the PTC account was one of the largest and one of the most reputed in the country in those years.

Under the benign chairmanship of Syed Nizam Shah, the outstanding marketing team of PTC was led by the debonair, intelligent Riaz Mahmood (alas, now departed), with the deceptively quiet, valuably insightful Saquib Hameed and the meticulously observant, sharply focused Taher Memon. The last named has carefully chronicled the crucial role of PTC , and others , in making cricket a national sport to equal and then overtake hockey in his book ” Another View ” . That ascendancy became possible only through PTV and PBC which took the images and sounds of cricket into the nooks and corners of the whole country. At MNJ we wrote, directed and produced numerous TV commercials with the pay-off line “Wills and cricket go together “.

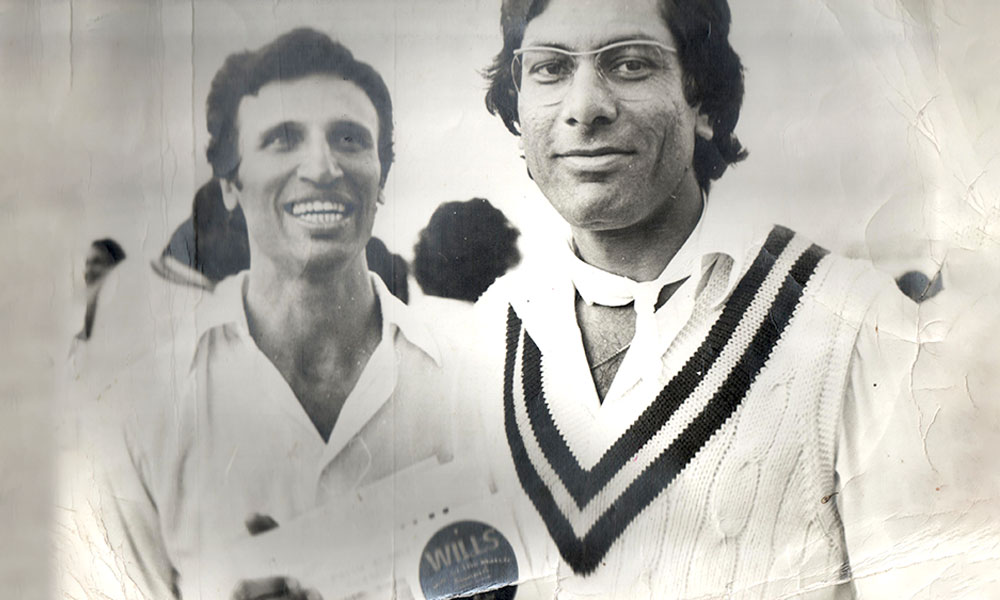

During the 1979 World Cup in England, this writer and the team filmed 5 leading Pakistani cricketers — Asif Iqbal, Zaheer Abbas, Majid Khan, Javed Miandad and a fast-rising all-rounder named Imran Khan for a series of five mini-portraits that became instantly widely popular through frequent screenings on PTV.

YouTube in 2023 gives access to at least 2 of them. The players were depicted in a range of family and play situations but never shown holding a cigarette, leave alone smoking one. Yet the synonmity of the brand and the player’s name was explicit and extensive, in return for a reasonable fee. Compared to today’s spoils a small sum. Current fees reportedly have thoroughly spoilt players, however well-deserved.

The popularization of cricket was greatly helped by a subtle aspect of General Zia ul Haq’s information policy: keep the attention of the masses diverted for long hours every day from the darkness of martial law, the execution of Z.A. Bhutto and it’s aftermath, MRD, etc. and from other plots contrived by the regime — by transmitting live coverage of a game that took hours and hours every day, not the fleeting 90 minutes of hockey or football.

For the record: Though this writer can rightly be charged for being an active party to the original sin , none of us involved in that initial phase of commercializing cricket wanted the creature of advertising to become a colossus on the field and in the media that it has become today. Can a tide be reversed, particularly when no state or private institution today in 2023 seems interested in moderating the surrender to pitches by brands while the pitches on which this addictive game is played, and the attendant values, receive far less attention.

The modern style of instant cricket such as T20s and The Hundred do provide a great degree of entertainment, but it is the format of Test cricket that requires real technique, talent and temperament and offers the most complex challenges to the batsmen especially when the task is to save the game from a difficult position. It is by no means an easy task to go out on day 4 or day 5, stay at the wicket for a considerably longer time on a deteriorating wicket and save the game for the team. Some of the finest aspects of the game such as the quality of bowling, the state of the pitch, the circumstances when the runs were scored and whether conditions make huge implications that cannot be found in the scorecard. These aspects can only be described in words. Here we look at the top 10 innings played by Pakistan’s batsmen that helped their teams avoid almost certain defeat.

To have a more meaningful quantitative analysis concerning bowling quality, the top four bowlers’ ICC ranking is taken into consideration at the start of the respective Test and the average is calculated. For example, Babar scored 196 against an Australian attack comprising of Pat Cummins, Mitchell Starc, Nathan Lyon and Mitchell Swepson. ICC ranking of these four bowlers at the start of the Test was 1, 16, 20 and 100 respectively. Taking a mathematical mean of these numbers 1, 16, 20 and 100 gives the average ranking of this attack as 34, which is a good indication of the quality of bowling Babar faced during his innings of 196.

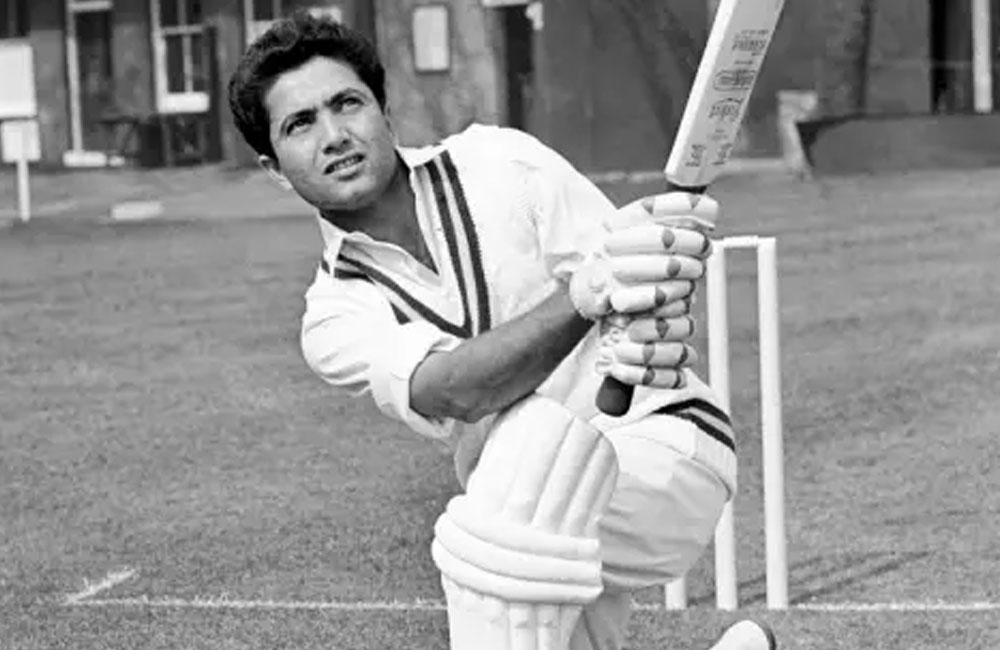

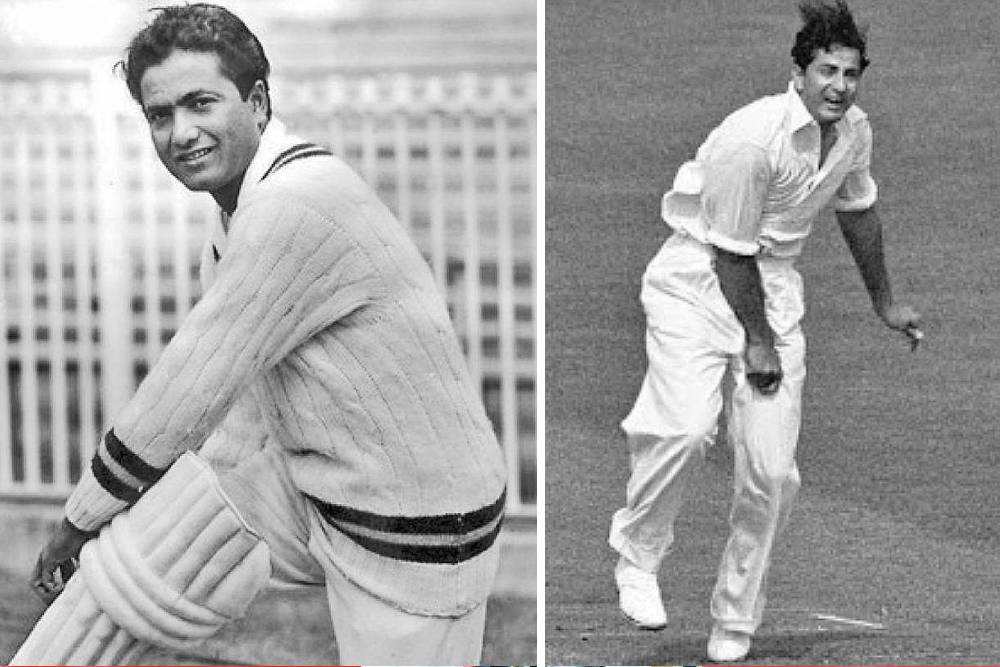

Hanif Mohammad, 337 vs West Indies, Bridgetown 1957-58

Pakistan and West Indies met for the first time in a five-match series in 1957-58. In the first Test at Bridgetown, West Indies rattled up a mammoth first innings total of 579-9 declared. In reply to this total, Pakistan was dismissed for just 106 in their first innings an hour after lunch on day 3. With a healthy first innings lead of 473, West Indies enforced the follow-on leaving Pakistan with a formidable task of saving the Test with over three days to go. Considering Pakistan’s dismal performance in the first innings, a thumping victory for West Indies was considered a foregone outcome. However, Pakistan turned the table upside down in the second innings. In a remarkable display of patience, temperament and technique, Hanif Mohammad stayed at the wicket for 970 minutes which remains the longest innings in the entire history of Test cricket. Hanif put up century partnerships for each of the first four wickets; 152 for the first wicket with Imtiaz, 112 for the second wickets with Alimuddin, 154 for the third wicket with Saeed and 121 for the fourth wicket with his brother Wazir – a unique record that has not been repeated ever since. Although the record for the number of balls faced is not available for early Test matches but Hanif’s innings of 337 is considered the longest innings in terms of balls faced. Hanif’s 337 saved Pakistan from a certain defeat.

An interesting incident often narrated is about a spectator who was watching Hanif’s innings on day three from a tree top outside of the ground. He accidentally fell from the tree and had to be admitted to a hospital. Two days later when he was fit enough to walk, he came to know Hanif was still at the crease. He climbed back on the same tree to resume his free viewing of this record-breaking innings by Hanif Mohammad!

Asif Iqbal, 152* vs Australia, Adelaide 1976-77

1976-77 twin tour to Australia and West indies is regarded as one the most demanding tour Pakistan ever had where Pakistan played high quality non-stop cricket against the best bowling attacks of modern cricket. The first Test against Australia at Adelaide produced very pulsating cricket where fortune changed on daily basis. Batting first, Pakistan got dismissed for 272 on day one with Zaheer scoring a classic 85 studded with some exquisite cover drive boundaries. In reply, Australia posted 454 with centuries from Ian Davis and Doug Walters. With 182 runs in arrears, Pakistan started their second innings in a much more resounding manner with all top order making a useful contribution. By the close of day 3, Pakistan had posted 140 for the loss of both openers Majid and Mudassar. The next morning, Zaheer continued with his first innings form, but he was dismissed by Dennis Lillee soon after completing his century. Asif, who failed to score in the first innings, joined Miandad at 236-4. Miandad departed with a gritty knock of 54 followed by Imran Khan (5). At 298-6, with a slender lead of 116 and only tailenders to support the last recognized batsmen, Asif had a formidable task at his disposal to bat long enough and give a challenging target to Australia in the fourth innings. Asif found a reliable partner in Salem Altaf as both took the score to 368 putting valuable 70 runs for the seventh wicket before Saleem Altaf was dismissed for 21. The next two batsmen, Wasim Bari and Sarfraz Nawaz went without scoring. At 379-9 with a lead of 197 and almost four sessions still to go, the match appears all in favor of Australia. Asif continued with his fighting innings, ensuring the last batsman and debutant Iqbal Qasim is not over-exposed to the bowling and completed his fighting hundred during the last session of the day. By the close of day four, Pakistan had reached 439-9 with Asif batting on 124. On the last day, Asif kept moving the score towards the safety zone. Finally, when Iqbal Qasim’s wicket fell at 466, Pakistan’s lead was already 285 with Asif remaining unbeaten at 152. The last wicket produced 87 runs at an almost runs-a-minute scoring rate. Asif’s never-give-in approach and meticulously protecting lower order yet scoring runs at every possible opportunity helped Pakistan to set up a good target to chase on the last day of the Test. Chasing 285, Australia was well placed at 201-3 but Iqbal Qasim took three successive wickets within a short period reducing Australia to 228-6. The seventh wicket pair of Marsh and Gilmour did not find scoring runs easy, hence decided to go for a draw ending Australia’s innings just 24 runs short of the victory target.

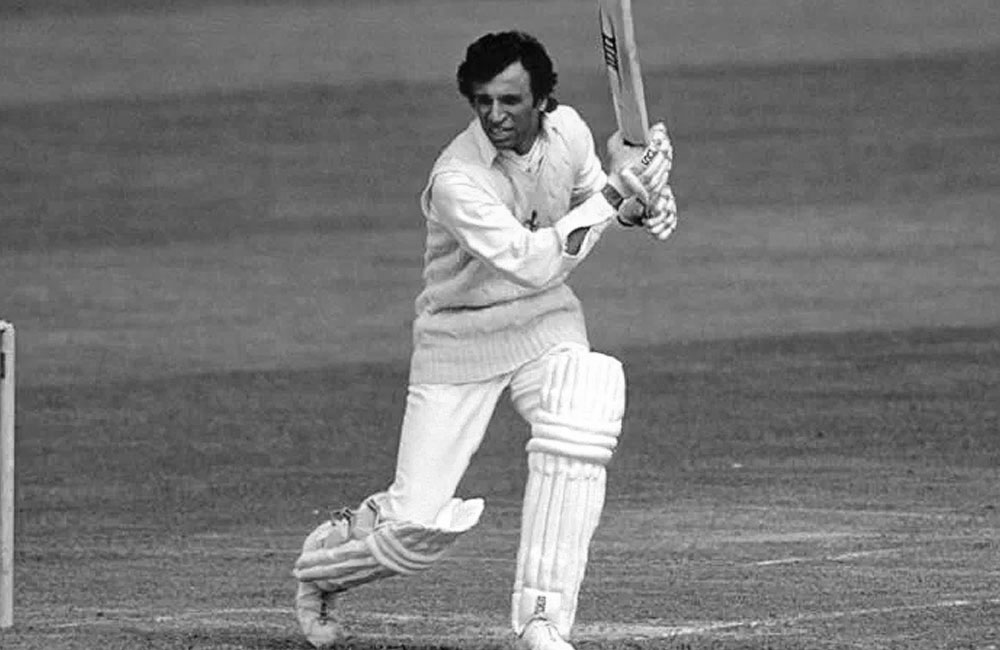

Majid Khan, 167 vs West Indies, Georgetown 1976-77

During the second leg of the 1976-77 twin tour, Pakistan batsmen continued to show their brilliance against West Indies’ ferocious bowling attack. On the opening day of the third Test of the five-match series at Georgetown, Pakistan was dismissed by the West Indian pace battery of Robert, Croft and Garner for only 194. West Indies made a strong reply of 448, gaining a first innings lead of 254. Facing the formidable task of saving the match, Pakistan openers started on an aggressive note, particularly Majid who decided to unleash his aggressive instincts on Colin Croft hitting him for four boundaries in his first over. Majid and Sadiq added 60 runs before Sadiq got retired hurt with his score on 22. Zaheer Joined Majid and they put on another 159 runs before Pakistan lost their first wicket at 219. Majid’s reached his hundred with 17 unstoppable cover drives and pull shots. He finally departed with his score of 167 ensuring Pakistan do not become an easy target for the West Indian fast bowlers. Pakistan finished their second innings at 540 thereby not leaving enough time for West Indies to go for the target in the 4th innings. All the three quicks who destroyed Pakistan in the first innings conceded over 100 runs in the second innings with especially Roberts who leaked 174 runs in the second innings got a good hammering by Majid and Zaheer. Majid occupied the wicket for approximately 6 hours and scored his career-best 167 with 25 boundaries, which is probably one of the best innings ever played by any Pakistani opener against one of the lethal pace attacks and that too without any modern-day protective gears like the helmet and various guards all around the body.

Javed Miandad, 102 vs West Indies, Port of Spain 1987-88

Even after almost a decade into Test cricket, Javed Miandad often faced a serious question regarding his ability to score runs against top-quality pace bowling under alien conditions. The tour to the Caribbeans in 1987-88 eventually proved Miandad is one of the best against any attack under any conditions all around the globe.

His scintillating century in the first Test of the series at Georgetown against the fearsome West Indies four-pronged pace attack of Walsh, Ambrose Patterson and Benjamin helped Pakistan win the test by nine wickets. In the second Test at Port of Spain, he played yet another top-class innings that saved Pakistan from a certain defeat. Marshall’s return further boosted the West Indies’ attack as they got out Pakistan for 194 in the first innings. With centuries from Viv Richards and Jeff Dujon, West Indies set a target of 372 to win in the last innings. Pakistan started badly and soon found themselves reeling at 67-3. Miandad, with his never-say-die attitude, had two match-saving partnerships; first, he added 90 for the fourth wicket with Saleem Malik and 113 for the sixth wicket with Ijaz Ahmad that helped Pakistan secure a draw. He batted for almost 4 sessions, facing 265 balls for a defiance inning of 102 – arguably one of the best innings he ever played in any away Test during his entire international career. His consistency made him a very special and reliable batsman in the history of the game. Javed Miandad is one of the two players (England’s Herbert Sutcliffe is the other one) whose average never dropped below 50 throughout his 17 years career.

Saleem Malik, 237 vs Australia, Rawalpindi 1994-95

One of the best batsmen of the 1980s and 1990s, Saleem Malik started his Test career in an explosive style scoring a hundred on his debut at the age of 18. A highly dependable top-order batsman who rescued Pakistan on numerous occasions also had lots of controversies attached to his name. The home series against Australia in 1994-95 was the tipping point of his career when three Australian players alleged that Malik had tried to bribe them to underperform on the final day of the first Test. In the next Test, he played one of the best innings of his career rescuing his team from a hopeless position to a respectable draw. Australia piled up 521 in the first innings and skittled out Pakistan for 260. Going into the second innings after follow-on with 261 runs deficit, Malik launched a counterattack with his career-best 237. His first fifty came up in just 49 balls with ten boundaries. His innings – that included 34 hits to the fence – was one of the most courageous match-saving efforts after Pakistan had followed on. Interestingly, Malik was dropped by Mark Taylor – one of the most reliable slip fields – when he was at 20.

This is very unfortunate Saleem Malik is more often remembered for all his shady involvement in match-fixing off the field rather than all his heroic on the field. His involvement and accusation not only came from Australian players but also from many other sources that pushed his career into obscurity.

Ijaz Ahmad, 120* vs Australia, Karachi 1998-99

Ijaz Ahmad lacked the flamboyance of Majid, Inzamam or Babar, had a somewhat clumsy batting stance, yet his temperament and resilience made him a solid middle-order batsman of his generation. Remarkably, he reserved his best against the best bowling attack of his playing time. An interesting fact not commonly known is his ability to score runs against mighty Australians. Out of 12 test hundreds scored by Ijaz, six came against Australia!

In the third and final test of the 1998-99 tour by Australia to Pakistan, Australia set an imposing target of 419 on day 5 of the match. There were only two possible outcomes: a victory to Australia or Pakistan batsmen playing out the whole day to save the match. At 35-3 within the first hours of play on day 5, an Australian victory seems a logical conclusion. Mohammad Yousaf also departed just before lunch to make Australia firm favorites. Then Ijaz together with Moin Khan put on 153 runs partnership for the 5th wicket to secure a respectable draw. Ijaz reached his century from 211 balls. He remained unbeaten at 120 when the game was called off after over no. 8 of the 15 mandatory overs. His counter-attacking innings included 16 boundaries.

Kamran Akmal, 109 vs India, Mohali 2004-05

Kamran Akmal is mostly remembered for his numerous dropped catches at vital moments that often cost the game to Pakistan. However, he was an aggressive batsman who played many important innings that saved Pakistan from certain defeats. One of such innings was his chanceless 109 at Mohali in the first Test of the 2004-05 series. With 204 runs in arrears, Pakistan started their second innings in a miserable fashion losing the top three batsmen with just 10 runs on the board. When Kamran Akmal came to bat at number 7, Pakistan’s lead was only 39 runs with four wickets in hand. Kamran and Razzaq dropped anchor and batted for more than two sessions on the final day. In the process, the duo added 184 runs for the seventh wicket in 56 overs with Kamran reaching his maiden test century. This partnership not only saved the game but eventually helped Pakistan draw the series 1-1. It would be fair to say this innings was one of the best played by any Pakistani batsmen on Indian soil.

Shoaib Malik, 148* vs Sri Lanka, Colombo 2005-06

The opening Test of the 2005-06 series against Sri Lanka produced high-quality absorbing cricket. Both the teams got dismissed under 200 in the first innings. Sri Lanka came back strongly in their second innings declaring at 448-5 riding on a scintillating century from Kumara Sangakkara who hit a magnificent 185. Set to chase 458 in the fourth innings of the match, Pakistan’s opening pair of Shoaib Malik and Imran Farhat made a slow but confident start putting on 59 in 27 overs. Shoaib Malik and Faisal Iqbal added 115 for the third wicket in almost 50 overs and another 84 for the fourth wicket with Inzamam that helped Pakistan save the game. Pakistan reached 337-4 in their second innings at stumps on the last day while chasing an improbable 458 runs target. Malik remained unbeaten at 148 from 369 balls and occupied the wicket for a little over eight hours to thwart Sri Lanka. His marathon innings was a classic reflection of temperament and endurance as he showed commendable foot movement against a very experienced Sri Lankan bowling attack.

Younis Khan, 131* vs South Africa, Dubai 2010-11

Whenever there is a discussion regarding top batsmen of the 21st century, Younis Khan’s name is often forgotten. His statistics, however, reveal a completely different story. He was not only one of the best produced by Pakistan but surely he stands amongst the greats of modern time. Younis Khan is the only player in the history of the game who scored test centuries in 11 countries! On numerous occasions, his innings made major contributions to winning or saving the games for his country. One of those innings came in the first test against South Africa in Dubai. Set to score a mammoth target of 451 in the fourth innings, Younis controlled the last day’s play striking 9 boundaries and 4 sixes to cruise to an unbeaten 131 to earn a respectable draw. Younis and Misbah added 186 for the fourth wicket unbroken partnership against one of the best bowling attacks of South Africa spearheaded by Steyn and Morkel. Younis Khan’s record in the 4th innings is indeed very impressive. There are only five batsmen who average over 50 in the 4th innings (qualification: minimum 1000 runs) and Younis is among one of those.

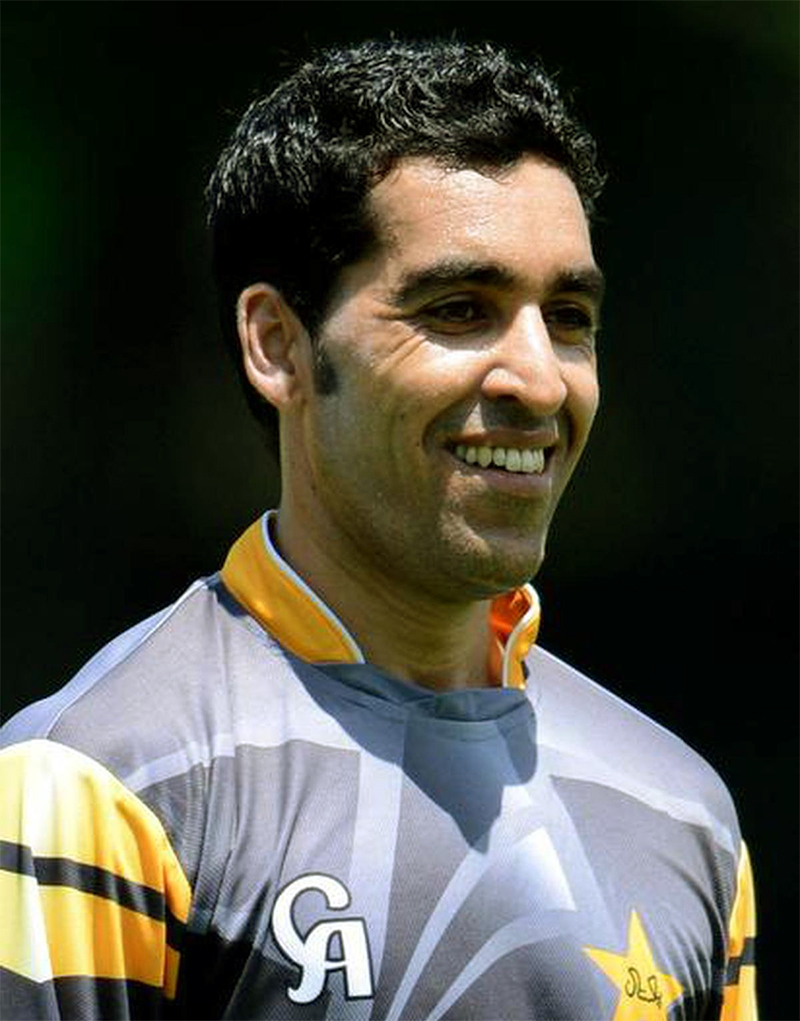

Babar Azam, 196 vs Australia, Karachi 2021-22

The tour of Australia to Pakistan in early 2022 witnessed some solid batting performance from both sides. In the second Test in Karachi, Australia set a mammoth 506 runs target. At 21-2 in the second innings and considering Pakistan’s dismal show in the first innings, it was expected Pakistan will crumble again, but Babar Azam’s heroic knock not only saved Pakistan from a certain defeat but he came very close to the unthinkable victory target of over 500 in the fourth innings.

The skipper played a true captain’s knock of 196 to stage an astonishing fightback. His innings of 196 helped Pakistan occupy the wicket for almost 6 sessions. He batted for 603 minutes and faced 425 balls. This is the second longest knock in the fourth innings of a Test after England’s Michael Atherton’s 185 against South Africa in 1995 which lasted 643 minutes. Pakistan’s innings consumed 171.4 overs. This is also the second best that a team survived more overs in the fourth innings to save a test match. The most is 218.2 overs by England against South Africa in the famous timeless Test in 1939. Pakistan finished their innings at 443-7 – just 63 runs short of the victory target. Babar got able support from Abdullah Shafiq (96) and Mohammad Rizwan (104). Interestingly, no other batsmen managed a double-digit score. He was given a standing ovation by the crowd and his teammates. The entire Australian team also applauded for his outstanding performance as he returned to the pavilion just four runs short of 200.

During the fourth Test match in India in March 2021, Rishabh Pant delivered a memorable innings that Sunil Gavaskar described as ‘the new India – a bold India’. This reminded Mark Nicholas of the iconic Sachin Tendulkar, who had astounded everyone by launching a ball straight over the sightscreen from 94 to his hundred.

The narrator’s fascination of cricket began the previous summer, when Brian Lara visited Oxford and his mother took him to watch a match. But it was the Pakistanis that truly captivated him in 1996, with five players averaging more than 60 in the series and an impressive supporting cast of Wasim, Waqar and Mushtaq. It was as if they were playing a different game, something that a 10 year old could barely understand.

One of the defining features of modern life is the presence of technology, which has become an integral part of day-to-day activities. The ubiquity of devices and tools has changed the way people go about their everyday lives. From communication to entertainment, technology has revolutionized the way we do things.

The way they played had a rawness to it, aggressive and confrontational but concealed by a languid elegance; they had the capacity to reach a higher state of being and, for those who watched, we beheld more than just a drive or a flick to leg – as CLR James expressed it, we saw how ‘a true expression of a man’s personality’ was demonstrated through cricket.

Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung spoke of how, unconsciously, he sought to find his personality which had been obscured by the pressure of being European; he remarked that the logical European doesn’t understand how human nature works, even though this rationality is obtained at the cost of his vitality. This could accurately explain the distinction between Atherton and Saeed Anwar.

What I understood then was that I was witnessing a period of liminality – a moment of quiet in the tumultuous history of Pakistani cricket. I was seeing an emancipation from its shady past; the cornered tigers of 1992 had broken the limits of Pakistan’s cricketing colonial roots and unleashed it to the public.

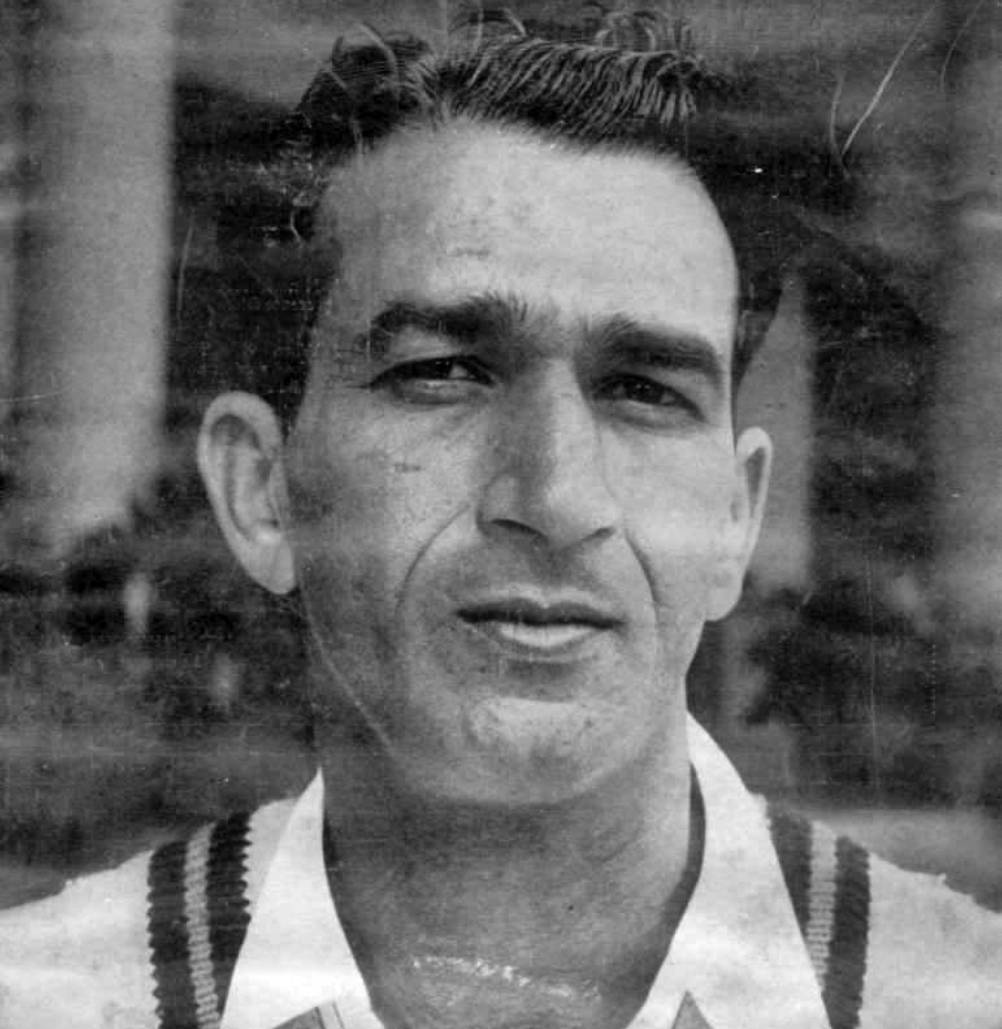

Hanif Mohammad and Fazal Mahmood were the first great Pakistani cricketers, but they still played in the English fashion defensively. While AH Kardar and Imran Khan were nationalists, they had been educated at Oxford and were thus a result of the English education system.

It is unknown how much of Khan’s career was driven by a desire to demonstrate his worth, as he was called ‘Im the Dim’ at Keble College. But AH Kardar was affronted at Donald Carr referring to him as ‘the mystic from the East’. On the same tour, the Englishmen captivated a Pakistani umpire, Idris Baig, and subjected him to what can be called as waterboarding. Carr, future secretary of the Test and County Cricket Board, later said of the incident, as an apology, ‘I think it was about the funniest thing I have ever seen in my life.’

The 1996 Pakistani team was derived from the normal people, as Naguib Mahfouz would have said, the ‘harrafish’ from the city. As James stated, ‘if style and daring can be both creative and effective it will be a demonstration of the idea that great cricketers and their style must be seen in relation to the social environment which produces them.’ Edward Said, in his book ‘Orientalism’, argued that the East was an invention of Europe. He cited Flaubert’s experience with an Egyptian courtesan, where he represented her in lieu of her expressing herself. This concept is echoed by Peter Oborne in ‘Wounded Tiger’, saying that ‘it is hard to come to grips with the set of values which led [Gatting] to take such a strong stand against allegedly poor Pakistan umpiring, yet be relaxed enough about apartheid to take a rebel squad to South Africa.’

The 2002 Indian team, with Ganguly standing on the Lord’s balcony, topless and waving his shirt around, was a representation of the Indian uprising of 1857. The ‘every man’ of the English team, Freddie Flintoff, compared having Ganguly as a teammate at Lancashire to ‘like having Prince Charles in your side…’. India, with Pant and others, stepped out of the colonial shadow, possibly encouraged by Brexit, Trump, and the western world’s poor response to the pandemic. This new India seemed to disregard the public school morals that, while out of date and elitist in most other aspects of life, are still adhered to in English cricket.

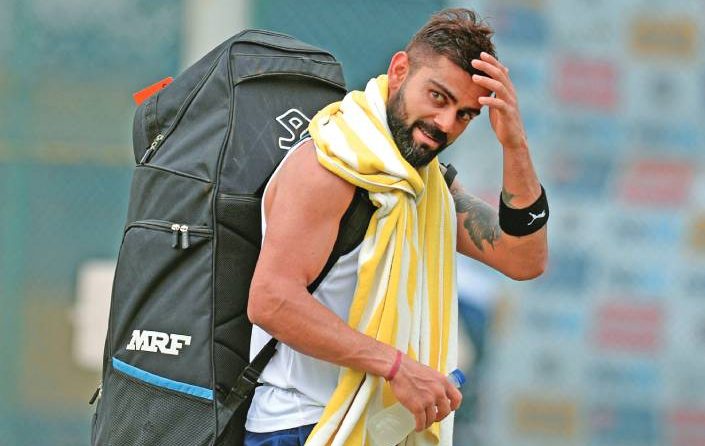

Virat Kohli, with his tattoos, his beard, his brashness, and his eloquence, is the epitome of this. He sets the moral code rather than following an archaic idea of it, and is an example of ‘style must be seen in relation to the social environment which produces them.’

Ten years before Pant demolished a tired English attack, India celebrated their World Cup victory at home by parading Sachin Tendulkar around the Wankhede Stadium on their shoulders. Kohli, when he was 21, said to a billion people that Sachin has ‘carried the burden of the nation for 21 years. It is time we carried him.’ His risk of a hundred for glory, like Pietersen, is thought of as outrageous by many. But the Indian team, now, is no longer surprising. Ashish Nandy said that cricket has become a South Asian game ‘accidentally discovered by the British.’ It is time to honour that.

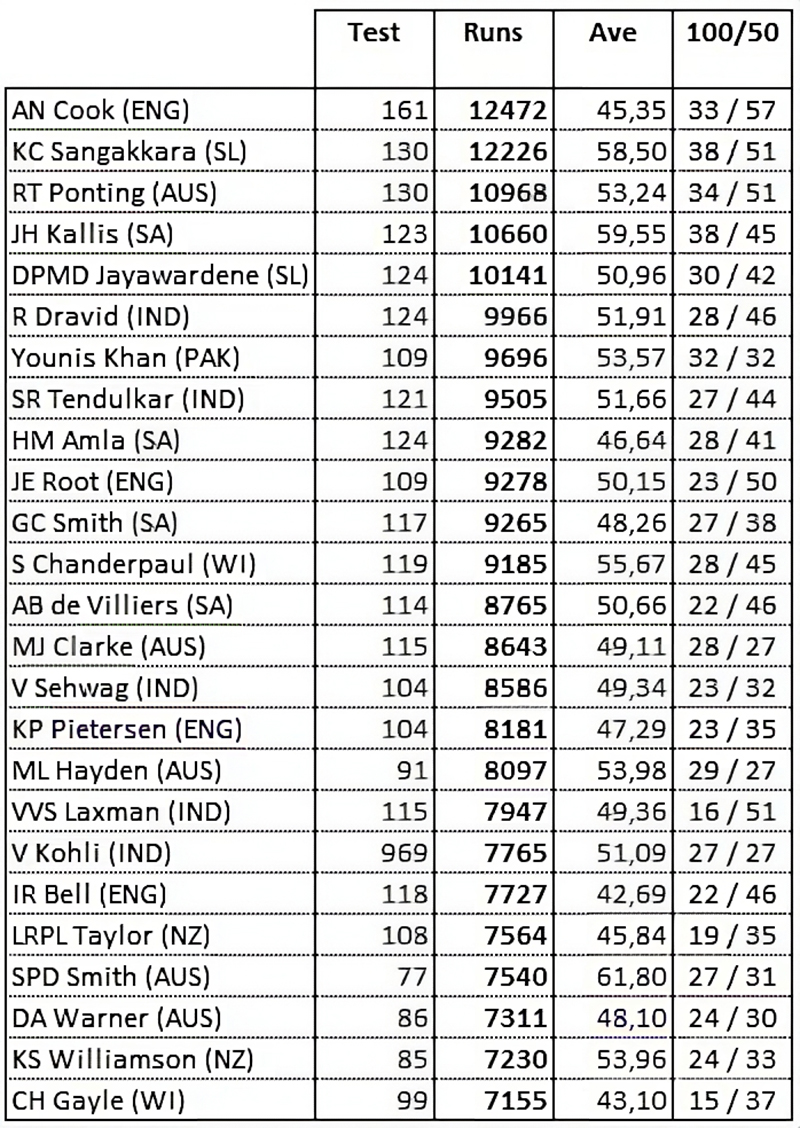

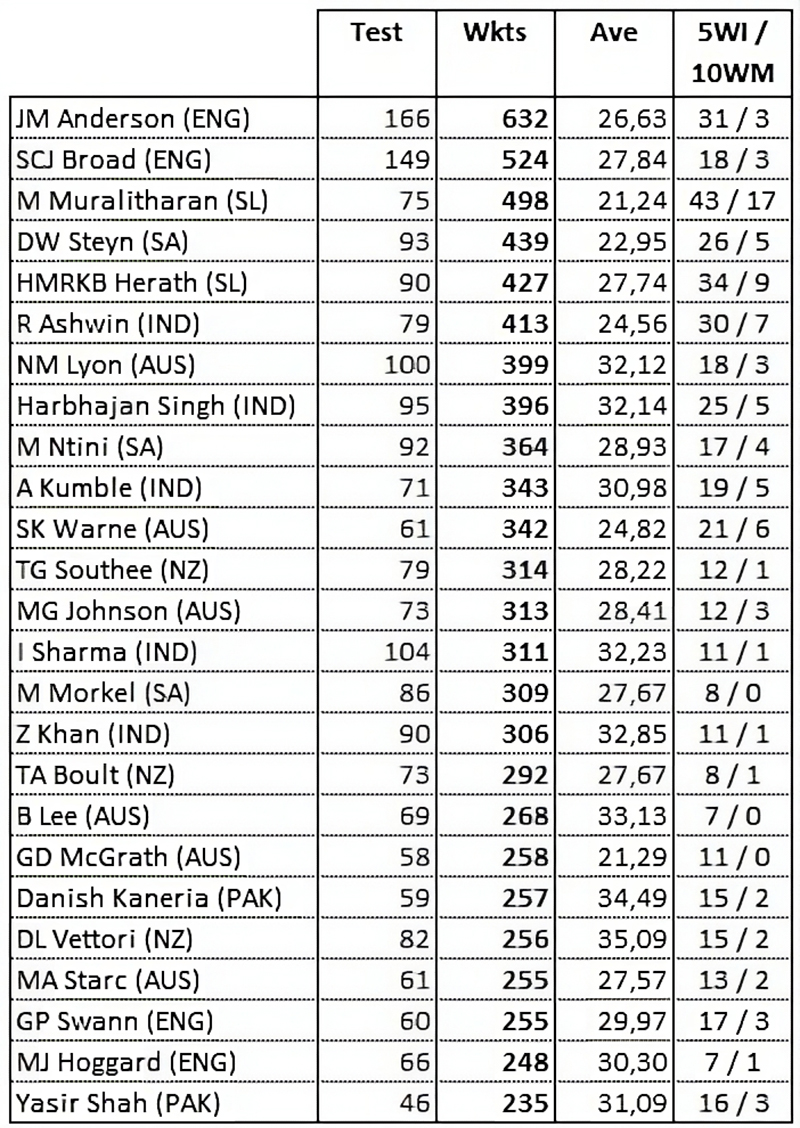

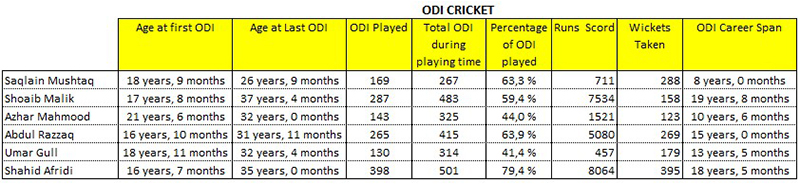

The other day when I was searching for leading Test batsmen and bowlers since the start of the 21st century, I came across something quite peculiar and somewhat expected. The top 25 batsmen and bowlers of this century only include one batsman and two bowlers from Pakistan! These findings prompted me to go a little deeper in search of the reasons why; are players from Pakistan not good enough with respect to talent and fitness to last for many years and make a lasting impression on the game like players from other countries? Perhaps a couple of bad performances are good reason for selectors to drop them prematurely, is it favoritism, nepotism, and policy of like/dislike instead of skill and talent or is it the preference of individuals for limited over white ball cricket over five-day red ball cricket that is hurting Pakistan cricket? The simple, short, painful and unfortunate answer to all these questions is a simple ‘yes’.

First, let’s look at these top 50 players – 25 leading batsmen in terms of runs scored and 25 leading bowlers in terms of wickets taken. These top 50 include 11 from Australia, 10 from India, eight from England, seven from South Africa, five from New Zealand, four from Sri Lanka, three from Pakistan and two from West Indies.

| Top 25 batsmen since 1st January 2001 | Top 25 bowlers since 1st January 2001 |

|  |

| Note: all statistics updated as of 30.09.2021 |

It is not surprising that 29 out of the top 50 belong to Australia, India and England. Consequently, these three teams generally occupied the top places in overall test ranking over the last 20 years. Pakistan and West Indies usually remained within the lower half of the ranking table and that poor performance also translates in the above table as well, with only five out of 50 players being either from Pakistan or West Indies.

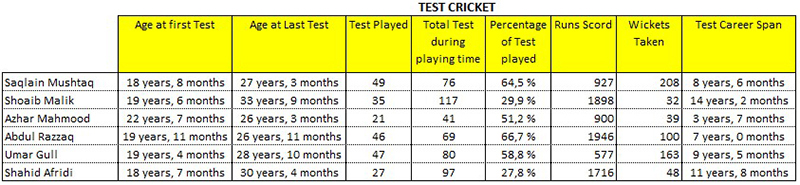

It is often said in Pakistan that the country is full of talent as far as cricket is concerned; it is just a matter of discovering and polishing the right talent, giving them confidence, and providing a conducive environment to prosper before they can deliver the desired results. This notion may or may not be true, but Pakistan has certainly seen many very talented players being wasted due to erratic selection policies, poor fitness level and immature decision-making on part of a few players to prefer limited overs cricket over test cricket. Here we will take a look at a few of those immensely talented players who represented Pakistan during the last 20 years and could have played for Pakistan for a very long period of time, but for various reasons their test careers were cut short. Although they all excelled in white ball cricket, they disappeared from the test scene with an average record, not having done justice to their true potential and talent.

|

Among them their average test appearance is just 37 tests with relatively short career span. However, their career records in limited over cricket in comparison to test cricket tell a different story both in terms of match appearance and career span.

|

Take the example of Shahid Afridi who failed to do justice to his real talent and leadership skills in Test cricket. He made his Test debut in Oct 1998 against Australia. Playing only in his second Test in January the following year, he played perhaps one of the best innings by any Pakistani batsmen on Indian soil by scoring a match winning 141 in Chennai where 102 runs came off boundaries. His typical flamboyant and aggressive style helped Pakistan win a close and tense match that earned him accolades from all over. Although during his initial playing days, he was equally effective in both Test and ODI but for reasons best known to selectors, he never became a regular member of the Test team even though his overall record in Test cricket is very decent with five centuries in only 27 Tests. When Afridi was appointed the captain of the Test team in 2010, he surprised everyone by resigning almost immediately and quit Test cricket for good. He continued to play only limited overs cricket and won many memorable matches for Pakistan.

Saqlain Mushtaq is regarded as one of the best off-spinners in the history of cricket. He is best known for inventing and introducing the “doosra”, a leg break delivery bowled with an off break action. He made great impact during his first domestic first-class season in 1994-95, taking 52 wickets that also earned him a place in Pakistan’s A team for a one-day tournament in Bangladesh. In September 1995, he took seven wickets playing for PCB Patrons against the visiting Sri Lankans. This performance eventually helped him get his Test debut in November 1995 when he was four months short of his 19th birthday.

Ever since he made his Test debut, he remained an integral part of the team. In ODIs, he used to bowl death overs, which are normally bowled by fast bowlers, but his extreme control over his line and variation ensured runs were not conceded at a higher rate during the last part of the innings. From 1995 to 2004, Saqlain played 49 Tests and took 208 wickets at an average of 29.83. Despite his great success in Test cricket, it is surprising to see he played his last Test at the age of 27. One bad series against India in 2004 sealed his fate. He took 1-204 in the Multan test that India won by an innings margin. Recurring shoulder and knee injuries coupled with selectors’ inclination towards leg spinner Danish Kaneria did not allow him to make a comeback to the Pakistan team. Therefore, his distinguished Test career came to an end while he still had a lot to offer to Pakistan. Many cricket experts believe it was unfair to discard him after just one unsuccessful series, yet in Pakistan cricket everything is possible at any stage. From the time he made his Test debut in 1995 until his last Test in 2004, Pakistan played all together 76 Tests, but he was only part of the playing eleven in 49 out of those 76 Tests. By any standard he was in the same league as Warne, Muralitharan or Kumble, who all finished with over 500 Test wickets and continued to play well over the age of 35. However, inconsistent and experimental selection policies halted his career with 208 Test wickets when he was only 27.

Shoaib Malik was discovered through Imran Khan’s Pepsi coaching clinic. In 1996 he appeared for trials held in Lahore and got selected for the under-15 World Cup, where he performed quite well with the ball. With the help of his good performance in the domestic circuit, especially with the ball, Shoaib got selected for the one-day team in 1999 and two years later made his Test debut against Bangladesh. Shoaib regards the late Bob Woolmer as one of the major influences for the improvement of his batting technique. He seemed to have benefited the most out of all the young players at the time when Bob Woolmer was Pakistan’s coach. Bob Woolmer always thought Shoaib was the best candidate to lead Pakistan for a long period of time. After the 2007 World Cup debacle, Inzamam resigned and Shoaib was appointed as Pakistan’s captain. Shoaib was also backed by Imran Khan, who believed Shoaib had a good and analytical cricket brain and could turn out to be a very good and long-term choice for leading Pakistan cricket. At the age of just 25, he was Pakistan’s fourth youngest captain. As expected in Pakistan’s cricket culture, being a very young captain and having many senior players in the team, his captainship tenure did not last long and two years later he had to step down. His brief spell as captain produced quite decent results, especially for ODIs where he led Pakistan to 24 wins out of the 36 games where he led Pakistan. All together he played only 35 Test matches in a career spanning almost 14 years. He had all the potential to become a very successful all-rounder and captain in the longer format (like Graeme Smith did for South Africa), but due to inconsistent policies and never-ending changes at the top where captaincy is almost always awarded based on seniority and age instead of merit and skill, Pakistan lost a very good player and captain to politics. During his 14 years playing span, Pakistan played 117 Tests, but he was part of the playing eleven in only 35 Tests, which meant he only played approximately 30% of the Tests that Pakistan played during his playing time. Had he been a regular member of the team and played until the age of 35, he could have played close to 140 Test matches!

Azhar Mahmood made his Test debut at the age of 22 against South Africa in October 1997. Batting at number 8 in his very first innings, he scored a blistering unbeaten 128 followed by an unbeaten 50 in the second innings. In early 1998 Pakistan made a return visit to South Africa where he scored two back-to-back centuries at Johannesburg and Durban. Wisden listed his innings of 132 at Durban (96 coming off boundaries) as the 8th best Test Innings of all time in its list of Wisden 100.

Wisden mentioned that “South Africa’s pace attack had more depth than at any other time in their history with Allan Donald and Shaun Pollock supported by Fanie de Villiers and Lance Klusener.’’. Despite scoring three centuries against very high-quality bowling in his first eight Tests, Pakistani team management persisted with him batting at number seven or lower positions, which did not help him establish and flourish as a regular and more useful batsmen. He was a very good seam bowler – especially useful in English conditions and a very sharp fielder at any position. Based on his cricket acumen, Lt- Gen Tauqeer Zia, who was the PCB Chairman in 2000, once said the board would choose the next captain based on merit and not based on seniority alone – and if people find the choice unacceptable, they will not be selected. Later, in front of many senior players – he told Azhar Mahmood that he would be the next Pakistan captain. It was reported that Azhar politely refused to accept the offer and instead supported Waqar as captain. Shoaib joined the team primarily as a bowler and turned out to be a fine all-rounder. Perhaps in the presence of Wasim, Waqar and Shoaib, it was hard for him to keep a permanent place in the team. When Wasim and Waqar retired after the 2003 WC, he could have been a regular member of the team. For reasons best known to selectors, he went out of contention for a comeback and subsequently a very promising all-rounder who could have played 100 Tests and 300 ODIs was lost.

Abdul Razzaq made his one-day debut in 1996 just one month before his seventeenth birthday and soon became a regular member of the ODI team. His fine performance as an all-rounder during his early days promised he would be amongst the best all-rounders for Pakistan like Imran Khan or Wasim Akram. A string of fine performances made him a regular member of Pakistan’s team for one day internationals. He played a vital part during the 1999 world cup in helping Pakistan to the final. Despite being one of the best all-rounders in the shorter format of the game, he had to wait for three years before he was selected for a test team against Australia in Brisbane in late 1999. On the same tour and during the Carlton and United one-day series, Razzaq came into prominence after hitting five consecutive boundaries in an over of Australian prime fast bowler Glenn McGrath. In 2000, Razzaq became the youngest cricketer in the world to take a Test cricket hat-trick against Sri Lanka (later Bangladesh’s Alok Kapali achieved a hat-trick while he was 17 and Naseem Shah broke that record when he did a hat-trick at the age of 16 against Bangladesh). He was so versatile and useful that he batted in all positions in ODIs or perhaps team management weren’t sure how best to utilize his skills to the team’s advantage. Since making his Test debut, Razzaq remained a regular member of the Test team and played 46 Test matches from late 1999 up to 2006. He is one of eight Pakistan Test players who have achieved the double of 1000 Test runs and 100 Test wickets. He was not selected for the 2007 World Cup team and that made him so dejected that he announced his retirement – a decision that he later revoked, as he played in both ODI and T20I but never got selected again for Test matches. This subsequently ended a promising Test career at the very young age of 26.

Umar Gul is yet another player whose real potential remained grossly under-utilized. He made his Test debut at the age of 19, played Test cricket for almost Ten years in a typical manner, which is a true reflection of uncertain selection policies of PCB and vanished from test cricket by the age of 28. During this 10 years’ period he was selected for roughly half of the Test matches that Pakistan played during his playing time. Nevertheless, his fitness issues were partly to be blamed for his early departure from Test cricket.

Coming through the history of Pakistan cricket, one can find quite a few players such as Wasim Raja, Aaqib Javed, Basit Ali and many more who had immense talent, but their performance did not match up to their true potential for various reasons that eventually cut short many glittering careers into an average one. Both Azhar Mahmood and Abdul Razzaq played their last Test match before their 27th birthday, which was a sheer waste of top-class talent that could have been avoided with more matured and consistent selection policies by PCB. Over the last few years, preferences by many players to play white ball cricket is negatively affecting Test team performance. This is the high time where the Board must intervene and come up with clear policies so that players do not choose if they want to play white ball or red ball cricket; they must prioritize what is good for the country rather than their individual preferences.

Arthur Mailey, the great Australian leg-spinner of the 1920s, was said to “bowl like a millionaire.” His successor, Clarrie Grimmett, was said to “bowl like a miser.”

Pakistan cricket has produced a full crop of millionaire and miserly spinners. In the first category are Abdul Qadir, his successor Mushtaq Ahmed, and, from the early days, the charismatic Prince Aslam, with his left-arm all sorts. (He also happened to live like a millionaire, even when he could not afford to.)

Standing out among the misers is the proud record of Pervez Sajjad.

His first-class career as a slow left-arm bowler spanned twelve years, from 1961-62 to 1973-74. During this time, he sent down the equivalent of 4550 overs, the great majority on sedated pitches in Pakistan, at a cost of 2.36 apiece, which earned him 493 wickets. Pakistan had a limited Test programme in the 1960s and he had some inconsistent treatment from the selectors. He therefore played only 19 Tests, in which he earned 58 wickets at 23.89 apiece, and his economy rate was only 2.04 per over.

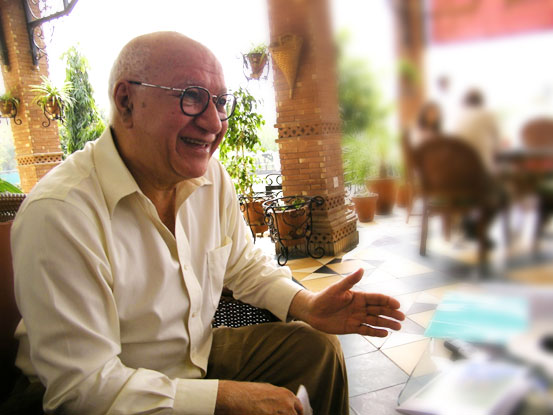

Pervez Sajjad did not look at all like a miser when I met him on a rare return visit to Lahore from his home in Paris. He was an affable, avuncular bespectacled man, soft-spoken but fluent. I could imagine him in one of those Parisian cafés on the Left Bank where intellectuals used to meet, arguing with Jean-Paul Sartre or Albert Camus about alienation and the art of the chinaman.

He was born in Lahore on 30 August 1942, one of seven sons of Mr Mir Khursheed Hasan, who was headmaster of Mozang Boys High School. It was a high-achieving family. His oldest brother was an army officer, Asghar Hasan, who was sent out to Amritsar at partition to bring Muslim refugees to Pakistan. He also went to Jullundur and collected several members of the Burki clan. Pervez Sajjad told me jokingly, “I can’t forgive him for this!” Ashgar eventually became a brigadier.

Pervez Sajjad’s next older brother was Waqar Hasan, a batting star for Pakistan in its first Test series during the 1950s. He scored over a thousand runs in 21 Tests and then established a successful business empire with National Foods Industries in Karachi. The third older brother was Pakistan’s greatest film director, Iqbal Shehzad, who made the classics Badnam, Beti, and Banjaran. Pervez worked for both Waqar and Iqbal at different times. He contemplated a full-time career in the film industry and took a co-producer’s credit on Iqbal’s first success, Badnam.

Pervez Sajjad made his breakthrough in cricket in his late teens, playing for the Universal CC in Lahore. He adapted quickly to the new turf wickets introduced into Pakistan at the time at the direction of President Ayub Khan (partly influenced by a comment from a distinguished guest, President Eisenhower, when watching the Karachi Test against Australia in 1959).

Pervez Sajjad made his first-class début in 1961-62. In only his second first-class match, for Lahore A against Combined Services in the Quaid-e-Azam Trophy he sent down 65 overs in both innings and captured 13 wickets for 98 runs – but his team still lost. In total his first season produced 30 wickets for 400 runs in five matches. He was not far off earning a place on Pakistan’s tour of England in 1962. His second season produced 16 wickets but he paid only 10.56 runs for each of them. He found time to take a degree in psychology at Government College, Lahore. Had he ever used this professionally? No. “Except perhaps against batsmen,” he added with a smile.

He made his Test début (with his friend Majid Khan) in the one-off Karachi Test against Australia in October 1964, securing the lone wicket of Peter Burge, caught by Majid. It was enough to earn selection for the subsequent tour of Australia and New Zealand. At Auckland he strangled the New Zealanders with figures of 12-8-5-4. No other Test bowler in history has paid so little for four wickets.

When New Zealand played three Tests in Pakistan in 1969-70 his 189 overs produced 22 wickets at a total cost of 342 – but the series was lost. Millionaire bowlers sometimes win matches on their own: misers need help from their colleagues.

Pervez Sajjad retired from cricket in 1974, ending a career which included four overseas tours for Pakistan. Like many ex-players he then worked for PIA, retiring as General Manager in Paris.

He enjoyed describing his secrets to me – not that there were many because his methods were simple. “I had a six-yard run-up, and tried to bowl at the same point every delivery, but mixing up my flight and my angles of delivery. Like Lance Gibbs, I occasionally threw in a slow beamer.”

The slow beamer is now banned but the rest is still an excellent formula for bowlers of his type, especially in Pakistan: immaculate line and length with minute variations. Because he has lived mainly overseas, he has not been able to contribute much to Pakistan cricket after his playing career. However, before the Asia Cup in 2007 he was invited by the then PCB chairman, Nasim Ashraf, to teach his miserly methods to some promising bowling prospects for Pakistan.

Unfortunately, for England, one of them was Saeed Ajmal.

Pakistan is a unique country where every person gives false impression that he is inevitable. Sharif family of Lahore has also been giving us the same false impression but Imran Khan’s Tehrik-i-Insaf broke their myth in the general election-2018.

The rise of Subhan Ahmed, the incumbent chief operating officer of the PCB, is inconceivable and baffling. With his humble education this intriguer/hugger-mugger started his career as a typist in the PCB. After being transferred to Lahore from Karachi he learned the art of buttering and showing a wily smile on his face

It was a warm July afternoon in 1992 when I was invited to a get together at Manchester’s Shabab Restaurant along with some members of the recently crowned world champion Pakistan cricket team which was in the middle of one of its most memorable, eventful and successful England tours to date.

The third Test was in progress at The Old Trafford and on its opening day, dear friend and swashbuckling opener Aamir Sohail had become the first batsman in 17 years after Sir Viv. Richards to score a double hundred on a single day in Test cricket.

The event, probably on the rest day of the match, was in honour of Pakistan’s greatest captain Imran Khan, who had opted out of the tour for personal reasons after winning the World Cup.

Having known Imran Khan closely for 3-4 years as a sports journalist back then, I was already frank and bold enough to muster the courage to move to his table soon after the formalities were over, in order to have a general conversation about his future plans as well as the ongoing series.

What followed next has become glued to my mind ever since and many of those who have known me closely have heard this story more than once over the years.

During that informal chat and general discussion, the conversation obviously led to his dream project of building the biggest cancer treatment hospital in Asia in the fond memory of his mother.

Sitting right next to him on a round table engrossed in a deep conversation I told him I wanted to share my personal observation about him. Go on, he said. “Skipper, (as we all used to call him unlike Captain or ‘Kaptaan’ he’s usually referred to these days), I don’t know exactly when, but I somehow see you ending up in politics in the coming few years”, I told him right afterwards.

Seemingly unsure, he smiled and responded to me in these words in Urdu: “Nahi yaar, barra gandd hai politics mein, mein kahan parron ga iss gandd mein” (No buddy, there’s too much trash in politics, so I don’t think I can ever get into it) was his reply.

“That part I don’t know, but I am sharing this thought as I am noticing a transformation in you ever since you have started this hospital project”, was my response to him.

The reason behind my conviction was simple. From an iconic superstar of legendary proportions, Imran Khan was arrogant and picky at the peak of his cricketing days. He was a habitual offender in slapping fans who dared cross a line or intruded upon his personal space or territory.

That arrogance was slowly being replaced by humbleness and an unusual grace, unforeseen before as he set out to raise funds for the hospital across the breadth of Pakistan. I think the sheer nature of the daunting task and the overwhelming love and support he received first hand from the poorest of his supporters was having an amazing impact on him. I had noticed that change and had a strange feeling that this man may have another role for the country. I’d be lying if I suggested if I had even the slightest idea that one day he would become the prime minister at that moment.

Call it another coincidence that almost four years down the road, I was sitting in the second row of a small hall at Lahore’s Faletti’s Hotel, in April 1996 when Imran Khan launched his political party Pakistan Tehreek–e-Insaaf (PTI), that finally swept into power last month.

After the press conference was over, I went to congratulate him, shook hands, gave him a hug and whispered in his ear: “Skipper, do you remember what I told you at Manchester’s Shabab Restaurant in 1992”. A big smile was what I got in return, I recall.

Twenty-two years down the road, it is a remarkable moment for Imran, and hopefully for Pakistan, as he takes oath as the Prime Minister of the country, against all odds after seemingly endless, bitter struggle against the status quo, injustice and corruption.

His elevation to the highest office gives me hope like millions of compatriots that Pakistan could embark on a journey of deservedly becoming a far greater country than what it is today. It gives me hope that one day justice would prevail in the society and the masses would get the same chance at life that is usually meant for the haves or the elite.

Imran Khan is a hard-core fighter. He is someone programmed to be relentlessly consistent and does not give up under any circumstances. Quitting in the wake of adversity is simply not in his genes. This has been evident throughout his illustrious sporting and political careers. Every time his critics wrote him off, he came right back with vengeance and achieved the unthinkable. A top-class performer, this man believes nothing is impossible in life.

While putting these thoughts together, I can recall many more incidents to shed light on the character of this extra ordinary man, who is indeed a rare breed from many aspects, but would do it separately on a different occasion.

Prime Minister Imran Khan, before earning this ultimate honour, you have already seen and enjoyed everything people usually dream of in life. It has taken you an enormous struggle spread over two decades to get to this position. No one denies your sincerity, but the fact remains that like all human beings you have been critically wrong in your judgment several times and committed blunders in your political career. It is now time for you to leave the petty issues behind and try to become a statesman from an opposition leader. Promote healing in the society please, so that the country and the government could focus on other pressing challenges.

This is your moment to do something truly amazing and change the direction of the country.

Hope is what keeps us all going. Here’s hoping God gives you the strength and wisdom to lead Pakistan to greatness.

Pakistan Zindabad!!

If Sethi, somehow, survives the demands of his removal, he should specially thank one man, the man named Sarfraz Ahmed, the one man whose part will be the biggest in saving his job.

With the emergence of new PM-elect and that too a former Cricketer of repute, it was just a matter of time that the air gets filled with demands of review of Pakistan Cricket and especially the top job in PCB, the Chairman of the board; currently occupied by Najam Sethi, the man who the supporters of the PM-elect have loved to hate in the recent years.

Sethi’s first taste of the job itself came in the wake of a regime change in Islamabad back in 2013

Earlier, it was Tauqeer Zia, in 1999, who replaced Mujeebur Rehman (after an interim period of couple of months with Zafar Altaf as the man in charge) when General Musharraf took over the reins of the country.

Not that the top job in PCB was either free of government influence or impetuous shakeups, ever. But the phenomenon of head of PCB getting rolled almost in chorus with the diplomatic head of the country was mostly unseen till the late 90s. Having said that, none of these extempore changes in 1999, 2008 or 2013 came only due to change of guards in Islamabad.

The 1999 transition came right after the shock defeat in 1999 World Cup final and all that noise of match fixing and corruption in years leading up to that debacle. Similarly, the changes in 2008 were preceded by a recent-past that saw Pakistan experience the humiliation of 2007 ODI World Cup, the loss in inaugural T20I World Cup as well as players like Afridi, Akhtar, Yousuf, Razzaq and Asif making headlines – more of national embarrassment rather than national pride – such as getting banned for threatening spectator with the bat, failing dope tests, sent home from a World Cup touring party or even giving up Pakistan career for a petty corrupt league – ICL.

The general mood in 2013 was not much different either. There were changes in coaching team, T20I captain, the selection committee and even the constitution and elections in PCB. In between, a strange run chase against England brought an end to T20I career of then captain, Misbah, another against Sri Lanka finished Pakistan’s T20I World Cup campaign and the strangest of them all, an unexplainable collapse against India spilling the rare chance of a whitewashing India in India, in an ODI series. Ironically, this was also the period when Pakistan played against South Africa a lot of matches and most of them finished in mis-matches.

All these episodes were preceded by a period of public dissatisfaction – even to the extent of public anger – and loud demands of changes in PCB setup without any link to changes in Islamabad. In fact, it were these demands and pressures that made the incoming governments rejig the PCB setup as a matter of priority.

Same could be repeated in 2018 as well, especially when the incoming Prime Minister is none other than one of the all-time great captains, the game of Cricket has ever produced.

Had the performance of Pakistan’s national team carried the same level of despondency, public disapproval and air of suspicion as it did during the periods leading up to the changes in 1999, 2008 and 2013, the chances of Sethi receiving a nod to continue would have been as bright as Imran Khan inviting Shahbaz Sharif to become the premier of the country in his place.

Adding into it the relationship between Sethi, the political analyst and Caretaker CM of Punjab in 2013, and the incoming PM and his followers, the voluntary resignation may have looked the only graceful option for Sethi.

Not surprisingly, the demands for removal of Sethi are neither unanimous nor loud enough to silence the counter-opinion. There are quite a few still demanding for his removal but it is fueled more by a context political in nature. On the other hand, there is equally popular sentiment to let him continue the job and that is coming more from the quarters who are evaluating the situation on purely cricketing grounds.

There are a couple of items on Sethi’s progress report as an administrator – the chairman of PCB – that stand out from the rest. The brightest is the return of international Cricket to Pakistan that saw World XI, West Indian and Sri Lankan sides performing for the first time on Pakistani soil since 2009. Ironically, the most unfavorable and critical comment on those efforts camefrom none other than the incoming Prime Minister himself. Remember phateechar and railu-katta?

That’s right, that comment. That sums up all the weight those efforts carry in this context.

The other item on the list is evolution of PSL from a desire to an infant and into a toddler. Without a doubt, it was Sethi’s relentless commitment to venture against all the hostile currents that played a pivotal role in making PSL what it is right now. The naysayers conclude that that’s the farthest that kind of effort could have gone; it has already peaked as an event and it has already slipped into the struggle of its survival. It will be a challenge, from administrative perspective, to keep the tournament going unless it moves to Pakistan – that links it back to the return of International Cricket to Pakistan, discussed above. Then there are those murmurs and whispers of transparency of expenses and procedures as well.

In a way, all his commitment to take PSL off the ground may still go completely against him, if examined with a lens of skepticism.

However, there is one aspect that is tough to deny. That is, the contribution of PSL in uplifting of Pakistan’s performance in International Cricket. Not long ago, the captains of Pakistan’s ODI and T20I sides, Misbah and Afridi, moaned about non-existence of future talent in Pakistan Cricket. The depressing statements came at the depressing end of respective careers. At the time, it looked just an expression of undeniable reality, said, with a holy purpose of helping the fans come out of denial. It took just a couple of seasons for the despondency of those comments to disappear in thin air, that too, right in front of those two experienced men.

Not that Pakistan had gone completely devoid of the talent in the previous years and Pakistan Cricket was not thrusting out, any more, the unseen talent that could excite the global audience. But what fueled this air of despondency, frustration and resentment was an endless repeat telecast of that talent recording yet another episode of unfulfilled promise.

As much as those talented boys themselves, the management and especially the leadership of the time was equally responsible for it. It seems, instead of carving glittering jewels out of raw gems, those leaders preferred to kill the subject by announcing nonexistence of any raw material with any potential in the supplies.

There was one man who disagreed with this summation, and probably the most. He took charge of all those half polished gems who showed glimpses of their potential in PSL, and made a spectacular chandelier out of them, a chandelier whose glaring shine eclipsed the brightest of the rivals at the exhibition of 2017 ICC Champions Trophy.

Sarfraz didn’t enjoy much of a say in team selection till the conclusion of second season of PSL. By that time, he had skippered a Pakistan side only 4 times – all in T20Is – once against England and in 3 T20Is against West Indies in UAE.

He took over Pakistan’s ODI team right after PSL 2, at a time when Pakistan was reeling at number 8 in the rankings. Fair to say, it was the time when he started to have his say in team selections. It was from that point onwards that the finds and stars of PSL started to feature more prominently in Pakistan lineups. Pakistan elevens started to include the names like Fakhar Zaman, Shadab, Rumman, Nawaz, Shinwari, Hussain Talat, Asif Ali, Sahibzada Farhan and Shaheen Afridi more frequently than all those could-have-beens of the past. And all these names justified their presence by playing their part in bringing the best resultsthe Pakistan Cricket has seen in recent years.

To produce results with a young side is an art and not every player – who ends up leading a side – manages to be an artist at it. Without the artistry of Sarfraz, the result with these products of PSL could have been the same as they were with higher rated talents under higher rated captains of the past. And with such a backdrop, the progress report of a chairman of PCB would not have been much different from those in 1999, 2008 or 2013, either.

It’s Sarfraz leadership that has provided the resilience to the foundations of Sethi’s cricketing estate. Without the results Sarfraz has produced in his short captaincy stint, the debate of Sethi staying or leaving the office might have been settled, long ago, and not in his favor. If Sethi, somehow, survives the demands of his removal, he should specially thank one man, the man named Sarfraz Ahmed, the one man whose part will be the biggest in saving his job.

A news item in the Indian media should open the eyes of all the Pakistan Cricket Board officials, including its chairman Najam Sethi!

The Committee of Administrators (CoA), running the matters of cricket in world’s richest board the Board of Control for Cricket in India, has directed the officials of the Board to spend from their own pocket in case they want to watch Indian team’s matches in England.

It’s in total contrast to Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) in which the theme is “maale-muft, dil-e-bayrehm” (free money so spend without mercy). Gone are the days when astute heads like Air Martial Nur Khan would never allow such free joyrides. But in the last two decades PCB’s money is spent like water as if the Board has broken the bank!

Pakistan will be wary of Scotland after they beat England in a 50-overs international for the first time in their history. Although T20 is a different beast, Scotland are ranked higher in T20 (11th) than in 50-over cricket (13th), though that did not stop them defeating the number-one ranked side in that format on their home patch in Edinburgh last Sunday.

As in the Test tour of England and Ireland, Sarfraz Ahmed will lead a young inexperienced side for two T20 Internationals against Kyle Coetzer’s Scotland. But although they will miss seasoned players like Mohammad Hafeez, the number one ranked all-rounder in white ball cricket, it does present the opportunity to blood young talent. Indeed, for recent debutants like Asif Ali, Hussain Talat and Shaheen Afridi, this will be their first outing overseas and a valuable lesson in their cricketing education.

Scotland will be confident and therefore dangerous after their unexpected but not undeserved win over England. They bat deep with Calum MacLeod, Kyle Coetzer, George Munsey and Richie Berrington, the most experienced.

MacLeod scored a stunning hundred in their 371-run total against England, a score which their workmanlike attack was able to defend despite the true pitch and small boundaries at the Grange ground in Edinburgh.

But with Sarfraz keen to finish the tour with a winning flourish and with Pakistan possessing three of the most dynamic T20 players in world cricket, Shadab Khan, Shoaib Malik and Faheem Ashraf, Scotland will need more heroics if they are to prevent Sarfraz’s team from enjoying a victorious farewell.