It was in 1980 that the phenomenon was noticed.

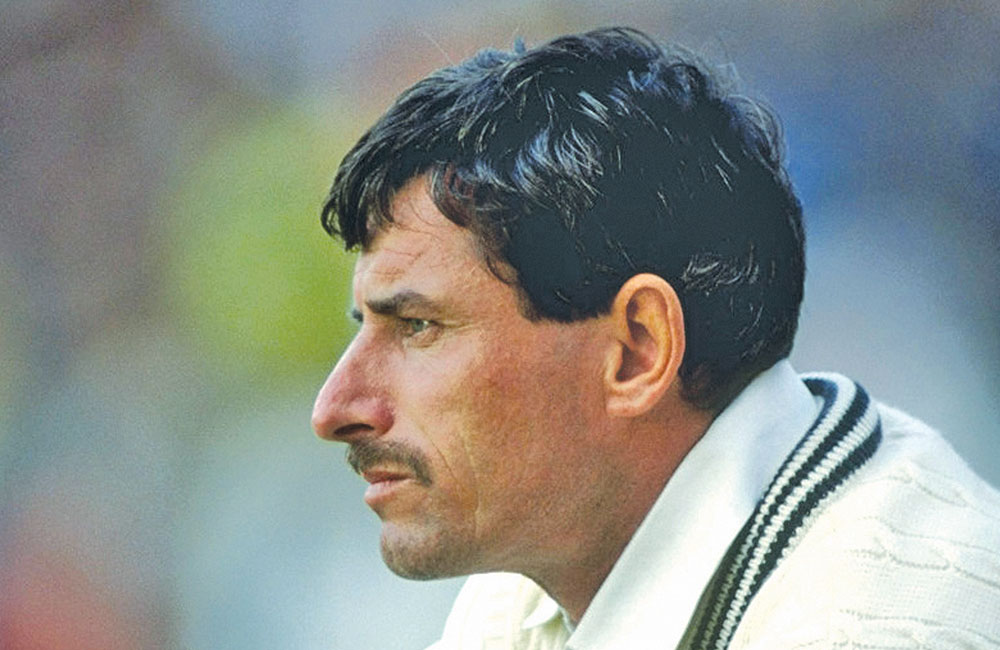

Of course, there was already Ian Botham. He had been around for three years or so. 5-74 on debut at Trent Bridge, against Australia no less. As the visitors of the 1977 summer focused more on signing clandestine contracts of the Packer Circus, Botham followed up his Nottingham act with a crippling 5-21 at Leeds.

And when England toured New Zealand that winter, the Somerset youngster hit 103 and captured 5-73 and 3-38 at Christchurch, followed by another five-for and a fifty at Auckland.

The following summer, as Pakistan visited, he hit 100 at Edgbaston. And if that was not enough, at Lord’s he hammered 108 and captured 8-34 in the second innings. By the end of the series, he had played eight Tests, averaged 49.88 with the bat and 18.05 with the ball.

It was difficult to maintain the sublime brilliance with both bat and ball, but Botham almost did so through the next 15 months. By the time he had won the Jubilee Test at the Wankhede virtually singlehandedly with 6-58, 114 and 7-48, he was unquestionably ruling the cricket world.

1,336 runs at 40.48 with 6 hundreds, 139 wickets at 18.52 with 14 five-wicket hauls, all within 25 Tests.

By early 1980, Botham had redefined the concept of the all-rounder. He captured the imagination of the cricketing world, especially the all-important English press. And he had reason to.

Pictures of him pushing a trolley alongside his wife Kate appeared in The Cricketer, even his footballing deeds were splashed across the sports pages of dailies. The all-conquering hero of the modern day. And he was given the captaincy against the incredibly powerful West Indies.

That marked a second chapter of the tale, but we need to pause here.

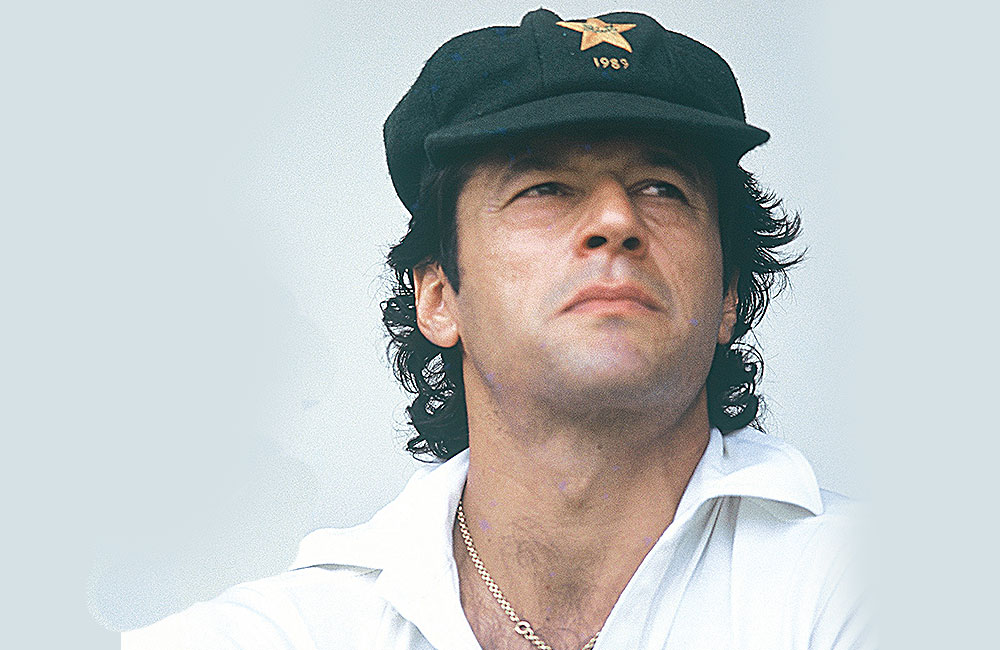

Curiously, Imran Khan and Richard Hadlee had already been around for a long, long time. Both were acknowledged as decent cricketers. It may be difficult to believe after all these years, but neither fit the bill as genuine all-rounders at the highest form of the game as yet.

Starting from 1971, Imran had played 29 Tests up to the end of the 1979-80 season. He was a force to reckon with as a bowler, his 118 wickets having come at a decent 29.94. But as a batsman he had crossed 50 only twice in 47 innings, averaging in the low 20s with a highest of 59. He was at best a decent, fast-improving bowler who could be handy with the bat and give the ball a wallop when required.

And by February 1980, Hadlee had emerged as an important cricketer for New Zealand. He had played 26 Tests since 1972 and captured 107 wickets at a decent but not remarkable average of 30.51. With the bat he was useful like Imran, averaging 20 for his 844 runs, hitting the occasional fifty.

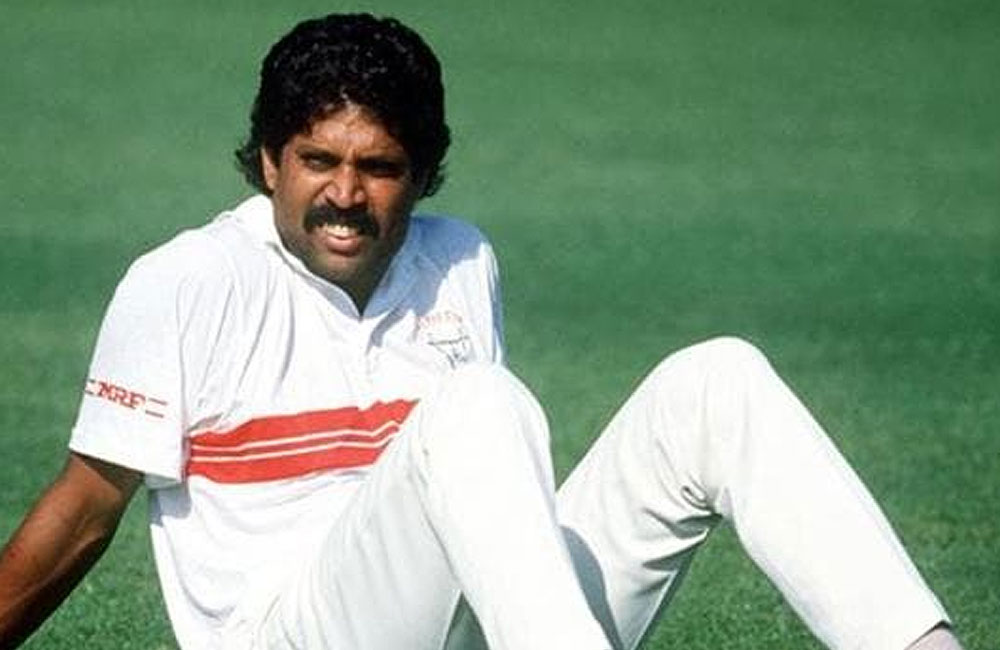

In contrast, it was Kapil Dev who took off the blocks at a nearly Botham-like speed. From his lukewarm debut against Pakistan in late 1978 until the beginning of 1980, India played a huge gamut of 26 Tests. Kapil hammered a hundred against the Packer-depleted West Indians who toured in 1978-79, amassing 329 runs in the series at 65.80 and capturing 17 wickets to boot. A decent outing in the English summer was followed by the visit of the Kim Hughes-led second-string Australian side and the extremely strong Pakistan team for two long Test series. Kapil captured 60 wickets in those 12 home Tests, while averaging well over 30 with the bat. He was the first pace bowler who had bowled India to victories and looked like doing so frequently, while his feat of 11 wickets and 84 at Madras against Pakistan was quite close to the Botham heroics.

So, in those 26 Tests Kapil had captured 103 wickets at 26.77, an unprecedented average and strike rate for an Indian pace bowler. He had also gone past 1,000 runs at a very creditable 33.37.

It was Kapil who provided the second dimension of the all-rounders’ world at that juncture, the only other man who could boast a hundred – a solitary one – to go with his wickets.

The figures given below are as things stood before the Jubilee Test of 1980 and the West Indian tour of New Zealand that season. This gives a good idea of how distinct Botham was from the rest, and how Hadlee and Imran both lagged behind until then.

The four all-rounders until early Feb 1980 (before Jubilee Test at Wankhede)

M | R | Ave | 100s | W | Ave | 5WI | |

Botham | 24 | 1222 | 38.18 | 5 | 126 | 19.59 | 12 |

Kapil | 25 | 1023 | 33.00 | 1 | 100 | 26.73 | 6 |

Imran | 27 | 914 | 23.43 | 0 | 112 | 30.25 | 7 |

Hadlee | 26 | 844 | 20.09 | 0 | 107 | 30.14 | 6 |

Things, as stated earlier, changed in 1980. Curiously Clive Lloyd’s all-conquering West Indians were at the receiving end on both these occasions.

In early 1980 they toured New Zealand. In a highly acrimonious series marred by Caribbean fast bowlers shoulder-charging umpires and uprooting stumps by kicking them, Hadlee’s 5-34 and 6-68 along with his 51 in the first innings engineered a one-wicket victory at Dunedin. He followed it up with a battling 103 at Christchurch. The third dimension in the all-round view was emerging.

That winter the West Indians toured Pakistan. Imran chalked up his maiden century at Lahore, and ended the series with 5-62 at Multan. He had checked the boxes as well. The world took notice. There were now four competing all-rounders, all quick bowlers who could bat very well.

All had now captured the imagination of the fans. Botham the incredible talent, the man who could do anything. Kapil the rustic face of primal energy, the oddity of a pace-bowling Indian who could hammer the ball when needed, an instant folk-hero among his countrymen who had never had someone quite like him. Imran with his Oxford-educated sophistication and smouldering good looks, his aura magical in the subcontinent, with a fair amount of mystique in Sussex where he plied his trade as well. And Hadlee, the silent, brooding Hamlet-like figure from a largely obscure New Zealand, who was busy making that also-ran cricketing nation a real force to reckon with.

It became a four-horse race. All four did rather remarkable things over the next four years.

After struggling with the yoke of captaincy in the West Indies, Botham continued with his magic tricks in the 1981 Ashes, especially at Headingley, hammering 399 runs and capturing 34 wickets. He amassed 440 runs in India and followed it up with a career-best 208 amidst his 403 runs at 134.33 when the Indians toured in 1982.

Imran flourished with each series, enjoyed a fantastic tour of England in 1982, but never did his star shine as spectacularly as against India in 1982-83. 247 runs at 61.75 and 40 wickets at 13.95, including 11-79 at Karachi and 11-180 alongside 117 at Faisalabad – the last performance as good as anything Botham had achieved. His 1981-84 figures read rather miraculous.

Kapil, thoroughly upstaged by Imran during the 1982-83 series, was nevertheless named captain after the tour. He hit a hundred in West Indies, averaging 42 and captured wickets at a brisk rate. The following summer saw him hit 175 not out against Zimbabwe in an epic innings at Tunbridge Wells. A few days later he held aloft the Prudential World Cup at Lord’s. When West Indies visited India in a so-called revenge series, they mauled the new World Cup champions in every possible way. Kapil’s bat went silent but he captured 29 wickets at 18.51.

In the meantime Hadlee spent the 1981-1984 period capturing 128 wickets at 18.75 while scoring his runs at 30.50. He was the most silent of all, but with his feats becoming achieved with metronomic regularity for Nottinghamshire as well he never remained away from focus.

The cricket world did not remember four all-rounders ever ruling the game with such consistency and panache. The template was redrawn. The term all-rounder somehow became synonymous with someone who bowled fast and batted flamboyantly.

The four all-rounders between 7 February 1980 to the end of the 1984 season

M | R | Ave | 100s | W | Ave | 5WI | |

Botham | 49 | 2937 | 35.81 | 8 | 186 | 30.76 | 12 |

Kapil | 37 | 1460 | 27.54 | 2 | 147 | 28.37 | 12 |

Imran | 24 | 1109 | 42.65 | 2 | 120 | 16.05 | 9 |

Hadlee | 24 | 976 | 30.50 | 1 | 128 | 18.75 | 12 |

But there were problems.

Botham’s number of wickets was indeed inflated because of the enormous number of Tests England played. Similarly, Hadlee did not get to play as many because New Zealand remained ignored even as they were starting to become a strong cricketing nation.

However, the England all-rounder’s bowling figures had become somewhat less intimidating. From a great bowler he had been reduced to a rather good one. The ability to swing was reducing in inverse proportion of his increasing waistline. His batting remained as feared, and he was capable of holding his own in the top five, something the others could not quite claim. But even to a generation not quite statistically savvy, the highs of Headingley were becoming enmeshed with misgivings about the future. His failures against West Indies, the major challenge of the era, was becoming more prominent. Besides, the disciplinary issues that could have been overlooked during the early days of his magic were coming to light as the spells he conjured up became less frequent and less hypnotic.

There were many who basked in the memory of his Headingley high, many still do. But the signs were becoming rather ominous.

Kapil had managed to maintain his momentum, but his performances had gradually become unidimensional. The West Indian tour of 1982-83 had been an exception. Generally during this period he either fired with the bat or the ball, seldom both.

And while Hadlee’s only vulnerability remained the few Test matches New Zealand played, Imran matched the New Zealander’s number of appearances because of a series of injuries. Stress fractures became the norm, he played several matches, including the 1983 World Cup, as a batsman. His bowling required remodelling. One wondered how many cricketing days he had left.

The next few seasons saw the early tables – of the late 1970s – turned almost totally.

Imran recovered, remodelled his action, missed quite a few Tests. But when he did play his performances remained phenomenal with both bat and ball. He captured 10 wickets at Leeds as Pakistan won by an innings, followed it up with 8 wickets at Birmingham and finished the 1987 series with 118 at The Oval. If he had retired without playing another Test, which he intended to do at the end of the Reliance Cup, he would have had 2770 runs at 32.97 with 4 hundreds and 311 wickets at 22.19. Those would have been thoroughly respectable figures, phenomenal even. But he did come out of the retirement he announced and his end numbers are more intimidating. More of that later.

Hadlee had continued in the same vein and could by now vie with Malcolm Marshall for the title of the best bowler of the world. He also managed to score his runs with an average in the high 30s, while taking five-fors at will.

While Kapil’s batting numbers are quite impressive during this period, he did capitalise on some of the most benign batting surfaces in India. At the same time, his bowling had deteriorated rapidly. He went through a barren period with the ball, including an entire home series against Australia without picking up a single wicket.

But the worst of the lot was Botham. His admission to cannabis use earned him a ban of six months. When he came back to dismiss Bruce Edgar off his first delivery, thus equalling Dennis Lillee’s world record number of Test wickets, he was asked “Who writes your scripts?” He broke the record shortly afterwards and then blasted a quick-fire half-century, pretending that everything was rosy yet again.

When he hit 138 in the first Test at Brisbane during the next Ashes series, it produced a further misleading impression that the happy days were continuing. That was the final century he scored in Test cricket. After that Brisbane Test he limped through the last five and a half years of his Test career managing 426 runs at 19.36 and 23 wickets at 48.82 over 16 Tests. The fall as steep as his phenomenal early rise, and far more prolonged in terms of time.

The four all-rounders from 1984-85 season to the 1987 season

M | R | Ave | 100s | W | Ave | 5WI | |

Botham | 21 | 898 | 28.96 | 1 | 61 | 36.08 | 3 |

Kapil | 26 | 1185 | 39.50 | 2 | 64 | 35.95 | 1 |

Imran | 19 | 747 | 39.31 | 2 | 79 | 20.08 | 5 |

Hadlee | 20 | 802 | 38.19 | 1 | 120 | 19.57 | 11 |

The final years of these four great cricketers need a deeper look at the numbers.

Botham’s decline has already been discussed.

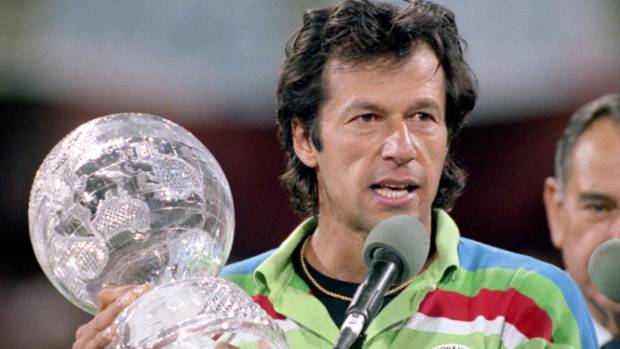

Coaxed back out of retirement, Imran remained a magnificent cricketer and his roles in mentoring, leadership and finally lifting the 1992 World Cup cannot be overemphasised.

On his return from retirement he started with 11-121 in the famous triumph at Georgetown, following that up with 9 wickets at Port-of-Spain.

However, while his numbers in this final phase read an impressive 51 wickets at 26.56, 23 of those wickets were captured on that Caribbean tour. His final 28 wickets came over 15 Tests at 34.87, and, more importantly, he bowled around 25 overs per Test during this final stage of his career, while he had bowled 39 per Test before that. He was no longer a genuine all-rounder in the true sense. He played more as a batter who was extremely canny with the ball, and in that role he was brilliant. Indeed, his final 18 Tests show more than 1,000 runs an astounding average of 61. He stuck to this role and perfected it. It is curious that he seldom ventured to bat above No 6 even during this period.

However, an average of 22.81 with the ball and 37.69 with the bat is unparalleled in Test cricket.

Hadlee retired first – if we discount the aborted retirement plans of the 1987 Imran. He was the only one among the four to do so in a blaze of glory. He had long gone past Botham’s world record number of wickets while the latter was still playing. He retired before the England all-rounder did, fully aware that the latter was too far gone to even try and catch up. In the process Hadlee became the first man to reach 400 Test wickets.

New Zealand did not play too many Tests and Hadlee had to stick around long and stay superbly fit to manage to appear in 86 of them. His 431 wickets came at a fantastic rate of more than 5 per Test, his 36 five-wicket hauls showing how important his role was in Kiwi cricket. New Zealand began to win with a semblance of regularity with his advent, and he accounted for 36% of the opposition wickets to fall in all Tests, and almost 41% in the victories. His batting, which can be justifiably said to be the least potent of the four, brought him an impressive tally of 3,124 runs at 27.16. He did not really decline and even in his batting he was ahead of Botham of the final days.

The four all-rounders from 1987-88 to the end of their careers

M | R | Ave | 100s | W | Ave | 5WI | |

Botham | 8 | 143 | 14.30 | 0 | 10 | 48.60 | 0 |

Kapil | 43 | 1580 | 28.72 | 3 | 123 | 30.26 | 4 |

Imran | 18 | 1037 | 61.00 | 2 | 51 | 26.56 | 2 |

Hadlee | 16 | 502 | 25.10 | 0 | 76 | 21.52 | 7 |

Hadlee’s numbers are put in perspective by Kapil’s efforts at going past his world record.

On 5 July 1990 Hadlee appeared in his final Test match. At that stage, Kapil was on 364 wickets having played 20 more Tests – a total of 106. The chase was hot for a while and then grew sluggish and finally painstaking. After a rather brilliant series in Australia in 1991-92, it was evident to all but the most devoted of fans that he was well past it. He played the occasional blinder, the 129 against South Africa at Port Elizabeth was a stunning innings as were the four sixes on the trot against Eddy Hemmings at Lord’s. But from the home series against England in 1993 onwards his bowling was only called upon when the ball was brand new or the tail was in. His bowling numbers did not suffer too much because he did not bowl that many overs.

It took him 23 Tests to take the 67 wickets to catch up with Hadlee, 24 to get past him and he retired after one more. It was not really the most glorious of exits. However, the fitness factor that allowed him to play 131 Tests as a fast bowler cannot be overlooked.

The final figures

M | R | Ave | 100s | W | Ave | 5WI | |

Botham | 102 | 5200 | 33.54 | 14 | 383 | 28.40 | 27 |

Kapil | 131 | 5248 | 31.05 | 8 | 434 | 29.64 | 23 |

Imran | 88 | 3807 | 37.69 | 6 | 362 | 22.81 | 23 |

Hadlee | 86 | 3124 | 27.16 | 2 | 434 | 22.29 | 36 |

The Legacy

All four of them were brilliant performers, three of them holders of the world record for the highest number of wickets, the other one generally acknowledged to be the best all-rounder alongside Garry Sobers and Keith Miller.

All four could do magical things with the ball, Botham and Kapil perhaps more potent in their early days, the skills of Imran lasting longer and Hadlee’s gifts not deserting him till his last day. All four were great strikers of the ball, Botham more adept to building long innings during the first half of his career, Imran during the last two-third of his, Kapil more prone to scripting the occasional innings of genius, Hadlee the same but a little less frequently.

The four of them co-existed with largely overlapping careers, and performed at simultaneous peaks during much of the eighties. This definitely had a far-reaching effect.

When we think all-rounders today we almost automatically think fast men who are good with the bat. Andrew Flintoff fitted the mould, Ben Stokes and Jason Holder do, Chris Cairns did.

When we look back the names that come to mind are Keith Miller, Alan Davidson, Tony Greig, Ray Lindwall, Trevor Bailey, Jack Gregory. Or the unfortunate South Africans we remember Mike Procter and Clive Rice. The ones more deeply rooted in cricket history can perhaps recall Trevor Goddard and, the more obscure, Tiger Lance. Each one of them was a fast bowling all-rounder fitting the template.

(When discussing Jacques Kallis we accept him but in the Sobers mould – a fabulous batsman who could also bowl like one of the frontline bowlers. That is a different category altogether.)

The combined influence of these four men in moulding our game-sense is so strong that we often ignore the claims of men like Ravichandran Ashwin, Ravindra Jadeja and Shakib-al-Hasan – champion all-rounders all. Even when we look back, Benaud comes across as the champion leg-spinner, and then we remember he used to bat as well. Ray Illingworth becomes the spinner who was the captain, Mushtaq Mohammad the superb batsman and captain who was handy with leg-spin. Further back Aubrey Faulkner’s figures make us take notice and then his being a leggie confuses us.

The spinner-all-rounder somehow is difficult to recognise because our perceptions have been long moulded by Botham, Imran, Kapil, Hadlee.

Very few have ruled the cricket world and the imagination like these four.

In his maiden press briefing Ehsan Mani, the chairman of Pakistan Cricket Board, had elucidated his specific mandate to revamp the Board. He had vowed to introduce a new system of good governance in the PCB and to run it on professional lines.

However, after two months in the office he has not succeeded to give any expressive direction which indicates that the PCB has at last seen a new system of governance and it is now being run in transparent and professional way.

It is all about old wine in a new bottle. The whole Mafia comprising incompetent hugger-muggers, which has already damaged Pakistan cricket in last two decades, is still around and enjoying their jobs without contributing anything noteworthy.

After his guru Imran Khan assumed the office of the prime minister of Pakistan, Zakir Khan has taken the saddle of Godfather of the Mafia from Subhan Ahmad, the most competent intriguer in the PCB. Zakir roams in the corridors of the Gaddafi Stadium like a warrior who has conquered the world and is enjoying frequent UAE visits. After all he is director international cricket.

Zakir was suspended or relieved from his job by Shaharyar Khan (reasons unknown to us) but apparently for his sheer incompetence and unwanted interference in the Board affairs. But once Sethi read the writing on the wall and quit the PCB in disgrace, Zakir was surprisingly reinstated. How? The acting/provisional chairman of the PCB, who happens to be the chief election commissioner of the Board also, reinstated Zakir soon after Imran Khan’s oath. Does the present PCB constitution allow a makeshift chairman to restore a suspended employee of the Board?

I remember when I was involved in my efforts to bring burly Ijaz Butt in the PCB, the summary was at the table of the then caretaker prime minister for his approval but he left it for the forthcoming elected prime minister. During Zakir’s over 30 months suspension, the PCB was functioning as usual and nobody felt his absence seriously. What was the necessity of restoring a suspended employee?

Zakir has spent twenty years in the PCB not because he was an educated former Test cricketer (two Test matches) but because of his friendship with Imran Khan which he always exploited to safeguard his personal interests. He once took an American returned former chairman of the PCB to Imran Khan’s residence and cemented his (Zakir’s) position in the Board. He was also spotted during the PTI’s sit-in (dahrna) in Islamabad but the then chairman couldn’t dare to take disciplinary action against him for attending a political protest.

Can anyone tell us what Zakir has contributed towards Pakistan cricket in last two decades? His only contribution in the PCB is to arrange invitation passes for the showbiz people during international cricket matches in Pakistan. Does Zakir’s academic qualification fit his job? We all know that Imran Khan has vehemently struggled for rule of law, justice and merit in the country in last two decades of his political life. I am sure that a dignified and honest Imran Khan would not like to be remembered as Godfather of any incompetent but intriguer.

Since his taking the saddle of the PCB, Ehsan Mani has done two amazing things. He issued sad media statements indicating that he is in the PCB to protect the Mafia. He issued statement in favour of cunning Subhan and brought Haroon Rasheed back at the Notorious Cricketers’ Academy (NCA). Haroon is an exhaustive YES MAN who can only impress bosses with his superfluous presentations raising their optimism. Mani has also desired to amend the Board constitution to facilitate a chief executive officer who could share his over-burdened responsibilities. Amazing! I want to remind worthy chairman of the PCB that he should recall Shakil Shaikh also, the erstwhile member of the governing board to complete his team for introducing good governance in the PCB!

Does Mani wish to slice his powers for the love of cricket or his business commitments don’t allow him to fulfill his responsibility as chairman of the PCB. A Chartered Accountant by profession and long-time UK resident, Mani is preoccupied with his numerous tasks. He is on the board of a number of UK companies mostly working in the banking and real-estate sectors. He is also the chairman of Galiyat Development Authority (KPK), member of board of governors of Shaukat Khanum Memorial Trust and member of board of directors of Biafo Industries Ltd in Pakistan. Certainly, such a pre-occupied wizard can’t give full time to Pakistan cricket! But Imran is Imran who still tries to find a Vivian Richards in every Mansoor Akhtar!

Mani needs a full time CEO to look after PCB affairs. Since there is no post of CEO in the present PCB constitution, so he wants an amendment. However, it would be a cruel joke to amend the PCB constitution for personal gain. The PCB needs to get rid of its fake constitution. Get rid of dummy board of governors. Kick out nominated members of the governing board. Bring back the elected general body. Neither an amendment will bring professionalism in the governance of the PCB or a tangible change in Pakistan cricket. Ehsan Mani Sahib you need to draft a new constitution of the Board. How long every chairman would continue to amend the constitution for personal gains?

It was a warm July afternoon in 1992 when I was invited to a get together at Manchester’s Shabab Restaurant along with some members of the recently crowned world champion Pakistan cricket team which was in the middle of one of its most memorable, eventful and successful England tours to date.

The third Test was in progress at The Old Trafford and on its opening day, dear friend and swashbuckling opener Aamir Sohail had become the first batsman in 17 years after Sir Viv. Richards to score a double hundred on a single day in Test cricket.

The event, probably on the rest day of the match, was in honour of Pakistan’s greatest captain Imran Khan, who had opted out of the tour for personal reasons after winning the World Cup.

Having known Imran Khan closely for 3-4 years as a sports journalist back then, I was already frank and bold enough to muster the courage to move to his table soon after the formalities were over, in order to have a general conversation about his future plans as well as the ongoing series.

What followed next has become glued to my mind ever since and many of those who have known me closely have heard this story more than once over the years.

During that informal chat and general discussion, the conversation obviously led to his dream project of building the biggest cancer treatment hospital in Asia in the fond memory of his mother.

Sitting right next to him on a round table engrossed in a deep conversation I told him I wanted to share my personal observation about him. Go on, he said. “Skipper, (as we all used to call him unlike Captain or ‘Kaptaan’ he’s usually referred to these days), I don’t know exactly when, but I somehow see you ending up in politics in the coming few years”, I told him right afterwards.

Seemingly unsure, he smiled and responded to me in these words in Urdu: “Nahi yaar, barra gandd hai politics mein, mein kahan parron ga iss gandd mein” (No buddy, there’s too much trash in politics, so I don’t think I can ever get into it) was his reply.

“That part I don’t know, but I am sharing this thought as I am noticing a transformation in you ever since you have started this hospital project”, was my response to him.

The reason behind my conviction was simple. From an iconic superstar of legendary proportions, Imran Khan was arrogant and picky at the peak of his cricketing days. He was a habitual offender in slapping fans who dared cross a line or intruded upon his personal space or territory.

That arrogance was slowly being replaced by humbleness and an unusual grace, unforeseen before as he set out to raise funds for the hospital across the breadth of Pakistan. I think the sheer nature of the daunting task and the overwhelming love and support he received first hand from the poorest of his supporters was having an amazing impact on him. I had noticed that change and had a strange feeling that this man may have another role for the country. I’d be lying if I suggested if I had even the slightest idea that one day he would become the prime minister at that moment.

Call it another coincidence that almost four years down the road, I was sitting in the second row of a small hall at Lahore’s Faletti’s Hotel, in April 1996 when Imran Khan launched his political party Pakistan Tehreek–e-Insaaf (PTI), that finally swept into power last month.

After the press conference was over, I went to congratulate him, shook hands, gave him a hug and whispered in his ear: “Skipper, do you remember what I told you at Manchester’s Shabab Restaurant in 1992”. A big smile was what I got in return, I recall.

Twenty-two years down the road, it is a remarkable moment for Imran, and hopefully for Pakistan, as he takes oath as the Prime Minister of the country, against all odds after seemingly endless, bitter struggle against the status quo, injustice and corruption.

His elevation to the highest office gives me hope like millions of compatriots that Pakistan could embark on a journey of deservedly becoming a far greater country than what it is today. It gives me hope that one day justice would prevail in the society and the masses would get the same chance at life that is usually meant for the haves or the elite.

Imran Khan is a hard-core fighter. He is someone programmed to be relentlessly consistent and does not give up under any circumstances. Quitting in the wake of adversity is simply not in his genes. This has been evident throughout his illustrious sporting and political careers. Every time his critics wrote him off, he came right back with vengeance and achieved the unthinkable. A top-class performer, this man believes nothing is impossible in life.

While putting these thoughts together, I can recall many more incidents to shed light on the character of this extra ordinary man, who is indeed a rare breed from many aspects, but would do it separately on a different occasion.

Prime Minister Imran Khan, before earning this ultimate honour, you have already seen and enjoyed everything people usually dream of in life. It has taken you an enormous struggle spread over two decades to get to this position. No one denies your sincerity, but the fact remains that like all human beings you have been critically wrong in your judgment several times and committed blunders in your political career. It is now time for you to leave the petty issues behind and try to become a statesman from an opposition leader. Promote healing in the society please, so that the country and the government could focus on other pressing challenges.

This is your moment to do something truly amazing and change the direction of the country.

Hope is what keeps us all going. Here’s hoping God gives you the strength and wisdom to lead Pakistan to greatness.

Pakistan Zindabad!!

After Imran Khan’s victory the days of shrewd and loud-mouthed Chief of the PCB and PSL Najam Aziz Sethi are numbered. His attempts to manage articles in print media and arrange tv programs highlighting his shallow achievements would not halt his imminent ouster.

According to media reports Ehsan Mani, a former president of the ICC, is the foremost runner for the lucrative post. It would be a good choice if he could maintain a reasonable balance between his PCB job and business engagements/interests abroad.

Media is also forwarding their favourite former Test cricketers. The name of a former cricketer turned commentator is also raised by some enthusiastic sports journalists. Passionate cricket followers remember that he had instigated a small group of team mates against Imran, particularly after his victory speech in the final of WC-1992. The name of a tainted fast bowler has also been projected in media reports. But he stands no chance because of his unfortunate tainted past.

After a determined political struggle of over two decades, the lady luck has smiled on Imran. After his political victory in the General Elections-2018 he is destined to become the first sportsman prime minister of Pakistan. Past and present Test cricketers are greeting the ‘Would be Prime Minister’ of the country. Just before the general elections some current cricketers had avoided to speak in favour of Imran in public fearing PCB’s displeasure. But after the results of the elections they hastily drove to Bani Gala to show their faces.

Imran’s contemporaries Abdul Qadir, Iqbal Qasim and Mohsin Khan, however, adopted a dignified path and congratulated their former captain through media. Anyhow an interesting race has started among the former Test cricketers to please Imran and win his support to get a place in the new PCB set up. Some one flew from Sydney and few others drove to his Bani Gala residence to express their greetings.

On a lighter note there is another overambitious and notorious blackmailer from Islamabad has also presented his candidature for the coveted PCB post. According to a media report, Imran Khan has signaled him to head the PCB. What a bizarre joke with Pakistan cricket! After his meeting with Imran, definitely not one to one, he wasted no time to manage to publish his wishful table story in a newspaper from Islamabad.

This man is associated with the PCB since the time of Dr. Nasim Ashraf and without any gap has remained the member of the Board of Governors. Imran would be the last person to allow this blackmailer to further spoil the Game of Gentleman!

Sethi has read the writing on the wall but adopted a Wait And See policy. It would be better for him to resign but grace and Najam Aziz Sethi are two things apart. Once it became clear that Imran is going to form government in Islamabad he is destined to be sacked.

Sethi’s case, as head of the PCB and the PSL, is a sheer conflict of interest which doesn’t come on Merit. How can an Editor-in-Chief of a weekly publication become the chairman of the PCB? How could he, chosen by 15 member governing board, become a chairman? That was only possible in convicted Nawaz Sharif’s democracy. But in the New Pakistan it would be hard to digest such a palpable clash of interest and dubious election.

In his recent editorial in his family’s publication, The Friday Times, he has accused that Miltablishment (Military Establishment) is behind Imran’s election victory. “No huffing and puffing will bring Imran Khan’s house down because he is protected and propped up by the Miltablishment,” the editorial said. Sethi has tried to establish that Imran’s victory is, in fact, Army’s ploy. After offering his wisdom through his editorial analysis if Sethi still expects that his seat in the PCB is safe he is insane. He should now devise plans to save himself from NAB and the FIA instead of predicting about Imran’s performance in government.

Further, he is misled by his self-assumed notion that interference from the political government would invite ICC’s reaction. He forgets that an Administrative Committee looks after the affairs of BCCI amid order of the Apex Court in India. The ICC did not interfere. Same is the case in Sri Lankan cricket. Why he is expecting something unusual from the ICC?

Who is going to head the PCB it is the sole discretion of Imran. Nevertheless, there is a dire need to purge the PCB. The dirt associated with the Board for over two decades needs to be flushed out. Those who have not made any notable contribution should be shown the door along with those who are facing the FIA and NAB inquiry.

Particularly, the den of inept officials of the National Cricket Academy must be removed immediately. Mudassar Nazar, a brilliant cricketer of the past whose cricketing insight was even praised by Imran in his autobiography, would try his best to save them. He would insist not to disturb likes of Ali Zia, Mohsin Kamal and a couple of other inept administrators and coaches at the NCA. This would be disastrous! These pigmies have contributed none despite of their over one and half year long association with the PCB. The complete revamp of PCB is the need of the day and Imran is bold enough to take such a decision in the larger interest of Pakistan cricket. Good Luck to the skipper of New Pakistan!

From Captain to PM, Imran’s rise is a story of struggle and resolve. A lot of people put it a struggle of 22 years …. 1996 to 2018 … but I would put it a journey of 47 years.

From an Atchison student to Oxford to country cricket and then graduating to Pakistan team at Edgbaston in 1971 both his phases were full of struggle.

But he challenged himself in equal terms and at both the platforms. He struggled with his action and once an umpire called, “right arm round the wicket, anywhere,” to suggest his wavering line.

Imran’s best came as captain. He became one by default, but he was destined to lead. From the outset he showed signs of “leader of men.” He led by example and the proverbial “from the front” was his strongest point.